Making a Masterpiece: What Writers Can Learn from Iconic Imagery in Visual Art

Everything I know about writing I learned by studying art. My knowledge of literature is limited in part because I’m dyslexic. As it turns out, this does not seem to matter. You can learn about writing by studying the masterpieces in art because every masterpiece, whether it’s a piece of music, literature, or visual art, has essentially the same ingredients.

Everything I know about writing I learned by studying art. My knowledge of literature is limited in part because I’m dyslexic. As it turns out, this does not seem to matter. You can learn about writing by studying the masterpieces in art because every masterpiece, whether it’s a piece of music, literature, or visual art, has essentially the same ingredients.

Tension is a primary component in all forms of art, achieved by the conflict between opposing elements. It’s the tension that holds our interest. In a masterpiece, the energy created by that tension reveals a universal truth. And a masterful artist does this without the viewer knowing it. She slips the message into our collective subconscious unnoticed.

A masterpiece becomes iconic when it is not only unique, but also strikes a quintessential cord. Iconic masterpieces are both ordinary and complex. Accessible to the public and widely praised by academia, they bridge the gap between popular and scholarly.

It’s a sweet spot every artist strives for, and writers would benefit by taking a look at how the masters of visual art achieve it. Here are some examples:

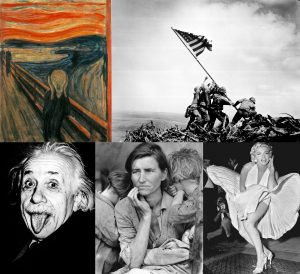

Edvard Munch’s The Scream sold at Sotheby’s auction house in 2012 for 119.9 million dollars, making it the most valuable work of art at the time. It is one of the most recognized images in the world. It’s been reproduced, written about, and parodied countless time. Andy Warhol, Gary Larson, and Erró are just few of the artists who have paid tribute to The Scream in their work. As an image, it is embedded in our culture.

Munch suffered from anxiety and depression and it’s believed that he feared he would fall prey to the mental illness that plagued his family. The expression of this anxiety is evident in his technique; the fierceness of his line work, his dizzying brush stroke, the fiery orange and yellow sky.

In contrast to the figure in the foreground, the two figures in the middle ground seem to be nonchalantly strolling along. Painted in a controlled manner, their relative normalcy is in opposition to the mood at the center of the painting. In the nexus of this contrast, the image deepens in meaning, and what could have been a cartoonish expression of anxiety becomes a frightfully searing depiction of alienation, the kind of alienation we all feel when trapped in the madness of our own thoughts.

Dorothea Lang’s iconographic photograph, Migrant Mother, is one of the most widely reproduced photographs in history. Lang took the photograph in 1933 as part of her work for the Farm Security Administration. The photograph immediately struck a cord and became an icon and symbol of the great depression.

The tension in this masterpiece is not overtly obvious because it’s so brilliantly embedded within the image. The central figure in this photograph appears lost in thought. Her mind adrift, she seems utterly unaware of the baby in her arms or the children at her back. Yet she is so firmly rooted to her circumstances that she seems to merge with them. They are barely distinguishable from her and she from them. At the intersection of this conflict is a universal message about motherhood. It expresses both the vulnerability and the strength required.

Consider the 1954 image of Marilyn Monroe posing on a subway grate. She’s holding her dress down as if she doesn’t want her dress to blow up, but why, then, is she standing on a subway grate? The image conveys conflicting messages, and in that tension it reveals what may be the universal male ideal of coquettishness.

Or look at Joe Rosenthal’s 1945 image, Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, in which six US marines are raising the American flag atop a mound of destruction. Take note of how heavy that flag seems. The raising of it is an expression of victory, but at what cost? In the schism between these two realities, we understand something about war.

United Press photographer Arthur Sasse’s 1951 photograph of Albert Einstein sticking his tongue out conveys the genius as a silly child. It’s a juxtaposition that we don’t expect and it humanizes him. We delight in the realization that we are, all of us, including him, just children at heart.

A masterpiece is a masterpiece is a masterpiece. In my study of visual art, unbeknownst to me, I was learning how to write. Conflict generates energy and that energy, at its best, reveals a universal truth. In almost every iconic masterpiece you will see this equation at work. Writers would be well served to seek out some of these iconic visual works and examine them closely.