Octavia Butler’s Notebook Represents All The Anxieties Of Writers Of Color

On its blog last week, the Huntington Library released previously unseen photographs of some of the late Octavia Butler’s papers, which the library catalogued after Butler’s untimely death nearly ten years ago. Included in the collection are some of Butler’s early science fiction stories, contracts, drafts, and notebooks, one of which caught the attention of nearly everyone on my Twitter feed last week.

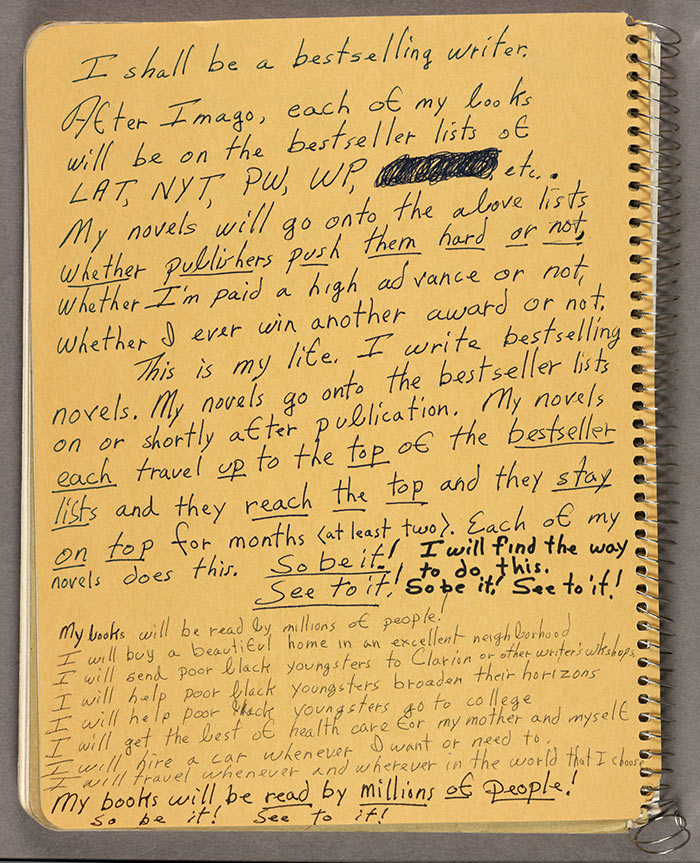

On the back of one of her notebooks, Butler writes:

I shall be a bestselling writer. After Imago, each of my books will be on the bestseller list of the LAT, NYT, PW, WP, etc. My novel will go onto the above lists whether publishers push them or not, whether I’m paid a high advance or not, whether I win another award or not. This is my life. I write bestselling novels.

While everyone celebrated the spirit of these words I’m embarrassed to say that I, on some gut level, cringed when I read them. I couldn’t articulate why. I love Octavia Butler—I love the Patternist Series, I love the Xenogenesis trilogy, I love the Parable series. I love Octavia Butler! So, what was my deal?

The notebook itself is such an incredible artifact, especially given the knowledge of all Octavia Butler accomplished with her writing, most notably the invention of the genre, Afro-Futurism, as we know it. The notebook is a key into Butler’s unbreakable spirit and psyche. At the bottom she writes,

The notebook itself is such an incredible artifact, especially given the knowledge of all Octavia Butler accomplished with her writing, most notably the invention of the genre, Afro-Futurism, as we know it. The notebook is a key into Butler’s unbreakable spirit and psyche. At the bottom she writes,

I will buy a beautiful home in an excellent neighborhood. I will send poor black youngsters to Clarion or other writer’s workshops. I will help poor black youngsters broaden their horizons.

There’s a certain kick-in-the-ass, coached fire to it: Get back to the page. Will yourself to success. No excuses—see to it! That’s the part that really got me: “See to it!” Having taught Butler before, and knowing what I know about her early struggles as a writer, I found myself equal parts impressed and depressed by that photograph, which burns with all the passion, love, and ambition for her own writing, but also the baggage that comes along with fighting—one weed at a time—through the woods that are “the business of writing.” A business which, for many years, wanted no part of what Octavia Butler had to offer and which—had it confronted a lesser spirit—might have squashed her altogether.

Underwriting the words on that page are the counterposing sentiments I see in many writers I know, especially writers of color: At one pole there’s, I just want to be okay; I want my family/community to be okay. At the other pole there’s, If I only reach the mountaintop I’ll be respected, valid, wealthy, etc.

I’ve known so many writers of color driven into severe debt or financial ruin in the pursuit of reaching the literary mountaintop. I’ve personally driven more writer friends of mine than I care to mention to hospitals and emergency rooms as a result of that pursuit as well, enough times to where I’ve wondered which ways “the business” of writing is not only excluding writers of color but actually killing them? Killing them emotionally and spiritually, sure, but also killing them in the increasingly unscrupulous grind of the adjunct scene, or the hyper-inflated New York rent scene, or the bar scene, etc. Sure, most all writers find themselves in a similar grind, but as organizations such as the VIDA count and others have quantified, “the business” as we know it is designed for some writers to grind less than other writers. And in the end the establishment alibis are all chalked up to market value if not chalked up to skill and apprenticeship—Does this writer come from an MFA? The Iowa Writer’s Workshop? A prestigious fellowship? Does this writer have the right pedigree? Do they write the kind of [MFA] story we typically publish?

For me, Butler’s saddest lines are these: “My novel will go onto the above lists whether publishers push them or not, whether I’m paid a high advance or not, whether I win another award or not.”

I loathe teaching my rookie students the “business” of writing, though of course it has to be done. Cover letters don’t write themselves. Neither do pitches, query letters, undergraduate contest submissions, etc. It’s not so much the content itself as the “business” factor to it all: this is how the sausage is made. And, of course, there are a million ways to mess it up, especially for my writers of color who are trying to advocate for themselves in order to carve out spaces for their voices in many elite magazines and journals that might be considered historically white and male-centric publications.

I always take the edge off “the business” talk by telling my students every way in which I, their fearless hero, have ever messed it up: addressing my cover to the wrong editor, addressing my cover to the wrong magazine, printing my cover on scented paper (working with what I had), stuffing a 20 page manuscript into a standard envelope (also working with what I had), writing a too-cool-for-school cover practically reeking of teenage hubris and Axe body spray, practically praying over a manuscript (instead of revising it) and being like, God, don’t mess this up for me. The anxiety of messing it up is always there though of course there’s always the other thing too: does anyone even want this story? To be blunt, this is the worst part about confronting the “business” of writing—who is our audience?

I like to tell my students to forget the audience in their first drafts. Mostly what I’ve learned is that you never really know who your audience is going to be anyway. I can’t tell you how many times someone’s linked to something I’ve written here and I’m like, “Really? That’s my reader?” It’s always a mild shock that anyone’s read anything I’ve written at all, though I’ll take what I can get.

Audience is, I’d argue, part and parcel of Butler’s own writerly anxieties in those lines. Earlier, she invokes the New York Times Bestseller list, judges, millions of people. And I wonder if that’s the thing that made me cringe. Can a writer of color afford to not care about audience? Is it shocking that Butler did? Is that somehow disappointing?

What I want to take away from Butler’s notebook is the exact thing that I want my students to cultivate and preserve in their own writing despite (or perhaps in spite of) “the business” talk we have. I want them to internalize the idea that to create something against all forces that would stymy it is a radical thing. And having created it—whatever it is—is something to celebrate. First drafts, half-drafts, all drafts should be celebrated.

“I will…I will…I will….” Butler writes toward the end. That’s the place I’m always trying to get back to—where my rookie writers already are, where the professional writers I know are always trying to be: where the fire is always glowing hot, where the next page burning to be written. That feeling like, Hey Prof! Check this out—