Raymond Carver, Gordon Lish, and the Editor as Enabler

As the story goes, most of what American readers love about Raymond Carver is not the work of Carver at all. All of his defining traits as an author—the minimalism, the colloquial roughness, the loud silences—none of these elements are particularly apparent before his work was edited (or, more accurately, revised) by the famously overbearing editor Gordon Lish. Many critics essentially credit Lish with Carver’s success. While some writers take umbrage with Lish’s slash-and-burn mentality as an editor, scant few critics contend that Carver’s writing was “better” before Lish got his hands on it. According to most, Lish did exactly what a great editor is supposed to do: fashioned Carver’s stories into more concise, more restrained, and yes, more literary versions of themselves.

As the story goes, most of what American readers love about Raymond Carver is not the work of Carver at all. All of his defining traits as an author—the minimalism, the colloquial roughness, the loud silences—none of these elements are particularly apparent before his work was edited (or, more accurately, revised) by the famously overbearing editor Gordon Lish. Many critics essentially credit Lish with Carver’s success. While some writers take umbrage with Lish’s slash-and-burn mentality as an editor, scant few critics contend that Carver’s writing was “better” before Lish got his hands on it. According to most, Lish did exactly what a great editor is supposed to do: fashioned Carver’s stories into more concise, more restrained, and yes, more literary versions of themselves.

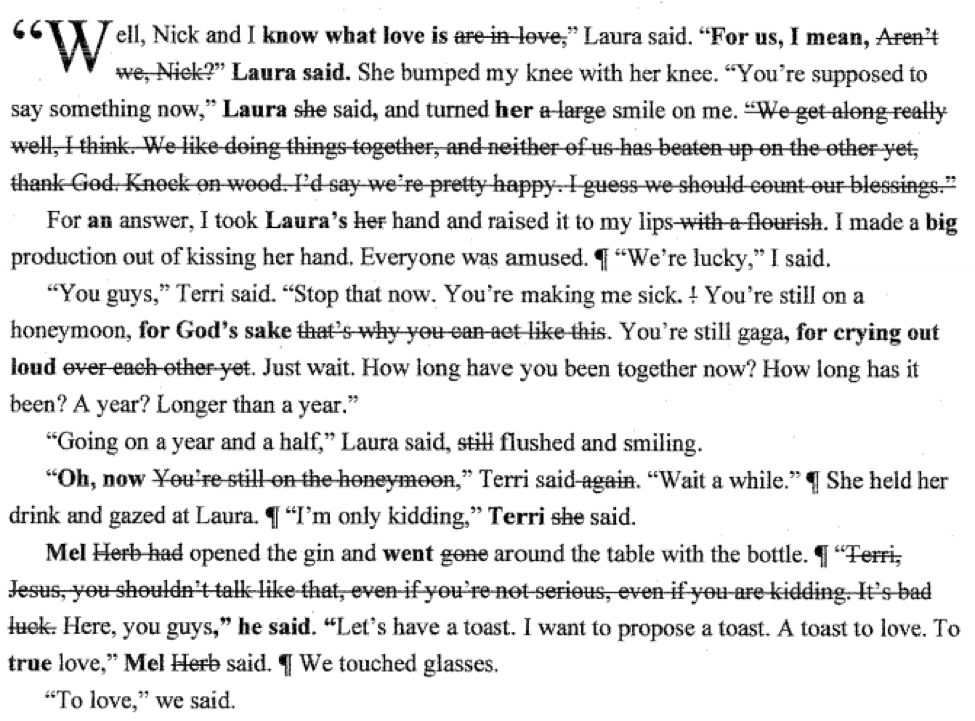

In his editing of the story “Beginners” (re-titled by Lish “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” henceforth WWTA), for example, Lish is quite plainly allergic to any kind of bald declaration of emotion, disdaining anything even resembling melodrama. For better and for worse, nearly every editorial choice he makes is aimed at changing—or, at the very least, muzzling—the emotion of the story. But while these edits successfully make “Beginners” more traditionally “literary,” they also take away from the raw power of the piece.

“Beginners” follows two couples at a horrifically tense dinner party. One of the couples, Terri and Herb (renamed Mel in “WWTA), immediately start bickering, and they never relent. Between the abundance of dialogue, the long monologues with almost no paragraph breaks, and the claustrophobic Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?-esque set-up, “Beginners” often feels more like a play than a short story. The emotion is heightened, the dialogue is often very explicit with the story’s themes, and the climax involves not one, but two extended dramatic monologues, complete with the dramatic reveal of a secret abortion. As Harvey puts it, pre-edited Carver tended towards resolutions with “the weightless intensity of a soap opera […] in which people broadcast their emotions to one another in stentorian italics.”

“WWTA” primarily uses Carver’s language, but still reads like a completely different story. Lish halved Carver’s long, flowing sentences and added many, many paragraph breaks. Character descriptions are slashed to the bare minimum, page-long monologues are reduced to a paragraph. He isolated character actions into their own paragraphs, affording them much more metaphorical weight and allowing much of the emotion to go unsaid. Perhaps most notably, he almost entirely jettisons the last three pages. He trades in Carver’s unabashedly theatrical catharsis for a quiet, ambiguous fizzle.

While melodrama is generally frowned upon in literary circles, and I would argue with good reason, “Beginners” is much more self-aware and deliberate than many critics give it credit for. On the second page, Terri and Herb have already traded several barbs in what was supposed to be a friendly conversation about the nature of love. When Terri accuses Herb of “dumping on her,” the narrator specifies that she “wasn’t smiling.” The couple tiptoes to the brink of social impropriety, and then Terri tries to change the subject for the sake of their guests. The narrator says, “She smiled now, and I thought that was the last of it.” When that is, decidedly, not the last of it, that line only serves to highlight that the couple is being rudely open with their emotions. Whatever your personal taste, that sense of melodrama is very much intentional. The reader is not meant to like these characters; rather, she is meant to feel as if she is at the worst dinner party of her life.

The never-ending tension fills the reader with a physical dread while reading “Beginners,” an effect that is almost entirely absent in “WWTA.” Not only are the explicit declarations of anger or sadness taken out, but the abundant paragraph breaks and section breaks serve to give the illusion that time has passed in between awkward moments, dissipating the tension and robbing them of their cringeworthy power. The insertion of white space might make the story more subtle, but it also serves to give the reader a break. Even though much of the dialogue is the same, if “Beginners” feels like the worst dinner party of your life, “WWTA” feels like every dinner party you’ve ever attended.

There’s no question that Carver came to regret the transformation of his work into a minimalist style. When he published the book Cathedral and, for the first time, didn’t allow Lish to significantly cut it down, he told The Paris Review:

I knew I’d gone as far the other way as I could or wanted to go, cutting everything down to the marrow, not just to the bone. Any farther in that direction and I’d be at a dead end—writing stuff and publishing stuff I wouldn’t want to read myself, and that’s the truth. In a review of the last book, somebody called me a ‘minimalist’ writer. The reviewer meant it as a compliment. But I didn’t like it.

That being said, it’s too simplistic to demonize Lish, and claim that Carver’s entirely unedited stories represent the “real” Carver. Every writer needs to be reined in by an editor from time to time, and the editorial relationship is a complicated one. As can be seen in their correspondence, Carver vacillated between loving Lish’s edits and despising them, between crediting Lish with all of his literary success and blaming Lish for suppressing his true voice. And even as I defend “Beginners” as an underrated work, I agree with many of Lish’s edits, particularly the title change and the deletion of the histrionic abortion reveal (as a rule of thumb, one page-long revelatory monologue is probably enough for one short story).

Ann Goldstein, who translated Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet, once referred to the translator’s role as an “enabler.” In a sense, editing should function something like a good translation: creating a version of a work that reproduces the intended effect on the reader. It’s easy to see why Lish is a legendary editor; however, I can’t help but wonder if there was a middle ground, a version of the story that preserved some of the unusual aspects of “Beginners” while tempering some of Carver’s more melodramatic tendencies. Then, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” could have been the white whale: a more effective and literary version of a remarkably different piece of literature.