The Remarkable Staying Power of Hisaye Yamamoto’s Seventeen Syllables

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, people were unable to tell the Japanese Americans apart from other Asian ethnicities, so they directed their hatred towards all Asians equally. Some Asians began wearing buttons stating their race—I am Korean! I am Chinese!—in an attempt to spare themselves from the discrimination. Today, when my news feed fills up with stories of yet another anti-Asian hate crime, I wonder if any of us have considered wearing buttons. But then I think that to do so would be insulting, a cowardly way out of our fear of being attacked by a stranger while simply walking down the street. Maybe wearing buttons wouldn’t matter anyway. Maybe this Asian hate isn’t actually about the pandemic or China. The present seems to be repeating the past when really the Asian hatred present in the past never went away.

For me, reading about the racism that Asians—especially Japanese Americans—experienced during World War II is personal. Both of my maternal grandparents were incarcerated in camps during the war, and that history has been passed down to their children and their grandchildren regardless of whether we recognize it. Though I may be a few generations removed from the trauma of the camps, its effect on my family is with me every day. That history has never stopped being relevant, though the ways it affects my family now may be harder to recognize. Still, it bubbles up in our need to always follow directions, and in my ever-present anxiety that always keeps me conscious of the concept of losing everything suddenly and unexpectedly.

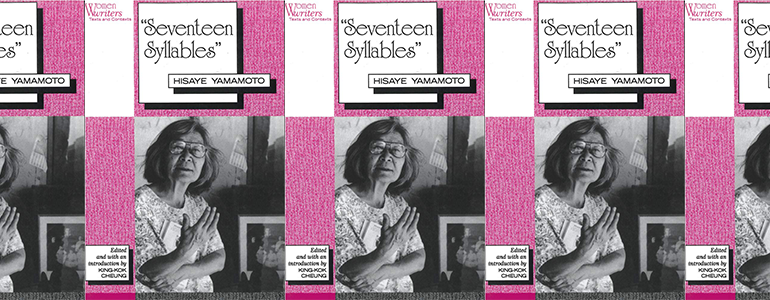

Hisaye Yamamoto, author of the 1988 collection Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, understands this. A product of the incarceration herself, Yamamoto’s stories focus on the camps, but also on the life of Japanese Americans after they were released, bringing a keen eye to the complex relationships that exist between first-generation Japanese Americans and their children. Perhaps what is most striking about Yamamoto’s stories, though, is how easily they could be written by a Japanese American author today, though many of them were written over fifty years ago, so focused are they on issues of race and the gendered expectations of women that still exist. Reading a Yamamoto story now makes you realize that her work was ahead of its time, but also that the struggles of the past are still with us in the present.

“Wilshire Bus,” for example, tells the story of Esther Kuroiwa, a woman who gets on a bus one day only to find herself in the middle of a racist attack on a Chinese couple sitting next to her. She worries as the white man in the seats behind them tells the Chinese woman, “Why don’t you go back where you came from? Why don’t you go back to China?” He mocks them by mimicking a Chinese accent, and he insults them with racial slurs. Everyone else on the bus, including Esther, stays silent. She wonders if “the man meant her in his exclusion order or whether she was identifiably Japanese”—a thought that is as naive as it is reactionary. When faced with possible discrimination, Esther hopes that somehow she can be exempt.

As the verbal assault continues, Esther is reminded of those very buttons worn by non-Japanese Asians to separate themselves from the Japanese discrimination associated with the war. She waffles between both wanting a button to differentiate her in this moment but also wanting to show her support for the Chinese couple. She even tries to “make up for her moral shabbiness” by silently trying to communicate her solidarity. The woman, however, is cold in her response. Eventually, the man exits the bus and another white man approaches the Chinese couple to reassure them that “we aren’t all like that man.” It’s a half-hearted attempt at comradery, and even though he is trying to do the right thing, his show of solidarity arrives just a little too late.

“Wilshire Bus” is a short story—it’s just a little over four pages long—and yet it packs an emotional punch that can be felt over seventy years from the date it was written. I cringe when I read it, having often heard the phrase “Go back to China!” directed towards me and my fellow Asians ever since I was a young girl. Nothing has changed in the way the hatred is portrayed. And while I have never been harassed on a bus by a white stranger looking to belittle me because of my skin color, I know people who have, and their stories stick with me. In fact, if you’re paying attention, the news in Asian communities here in the United States is filled with incidents just like this one. Nothing has changed.

At the end of “Wilshire Bus,” Esther reaches her destination “filled once again in her life with the infuriatingly helpless, insidiously sickening sensation of there being in the world nothing solid she could put her finger on.” Which is typically the case after any kind of racist interaction like this one. It rips you from yourself until you are nothing but a body meant for ridicule, standing silent and helpless while the world looks on and does nothing. Of course, Yamamoto’s decision to make her main character a woman is also significant here, as the helplessness women feel after this particular kind of humiliation is always doubly enhanced.

Complex women fill Yamamoto’s stories. There is Tome, the haiku writing mother of “Seventeen Syllables,” whose husband believes that Tome’s duties as a mother and a wife must eclipse her desire to write poetry. “The Legend of Miss Sasagawara” tells the chilling tale of a mysterious woman incarcerated during the war who experiences fits of undiagnosed madness that seem to be either a product of lost love, lost children, or something even more deviant. And then there’s Mrs. Hattori in “The Brown House,” who finds herself married to a gambling addict and who must watch as her life and the lives of her children and husband become lost to her husband’s uncontrollable addiction. Reading these stories, these women don’t feel any different from many of the women that exist today, trapped within their own lives and subjected to a whole host of gendered problems that remain unsolvable.

“The High-Heeled Shoes, A Memoir” is the story that feels the most topical in the way it navigates the predatory behavior of men alongside the fear women carry with them whenever they find themselves confronted by them. In a lot of ways, it is a piece that shares many traits with Joyce Carol Oates’s famous story “Where Are You Going, Where Have you Been.” Both revolve around a young girl home alone who encounters a devilish man that tries to seduce and deceive them. Oates’s story famously ends with the young girl, Connie, leaving the house supposedly to make her way to Arnold Friend and his waiting, sinister car, but Yamamoto’s story revolves around a man who is far less visible.

The narrator of the story answers a phone call one morning from a man named Tony. She does not know this man, and yet he tells her, “There is a certain thing which you and I alone know.” He is a smooth talker, kind even, and the narrator entertains his conversation, unsure of where it’s going. Even so, she feels uneasy conversing with him, and when she eventually gets fed up with his games and asks just what it is that he wants, he tells her. “I see that the certain thing alluded to by the warmth of his voice is a secret not of the past, but, with my acquiescence, of the near future,” the narrator says. Rightfully put off by Tony’s lewd request, she hangs up on him, but the feeling of discomfort she has gotten from just their brief, verbal interaction leaves her feeling uneasy.

This inappropriate phone call forces the narrator to remember all of the other times she and the other women around her have been subjected to the violent sexual behaviors of men. First there is the matter of her family member Mary who was nearly raped during an altercation in a parking lot. The man who attacked her “gave her a choice between one kiss and rape.” She chose the kiss, but when she went to report it to the police, she found that they did not take her assault seriously. She was promised that there would be extra patrol cars near where the incident had occurred, but Mary never saw any. Instead, she and her women friends were forced to find other, safer ways of getting around town. The narrator also remembers a man who flashed her from his car while she walked to work one morning, and notes that “there was the man in the theater with the groping hands. There was a man on the streetcar with insistent thighs.” The narrator lists all of her encounters with men invading her personal space to touch, grope, graze, and fondle parts of her without her permission. She worries about her sisters and whether Tony will come for them too. She wonders if she should call the police. In the end, though, she decides to do nothing—a powerful decision reflective of the level of seriousness with which society takes women’s stories.

When I first read “The High-Heeled Shoes, A Memoir,” I had to check to see when it had been written, so strangely contemporary was it that I almost couldn’t believe it belonged to the 1940s. And yet, of course it did—of course this sort of brazen sexual harassment has been going on for decades, centuries, forever. The problems of Yamamoto’s time are still the problems of today, and it is remarkable to think that we can pick up literature that is closer to being a century old than not and still see ourselves and our lives reflected within its pages.

I am in awe of Yamamoto. She is a woman who endured many hardships throughout her life, and yet she maintained a profound connection to the injustices of the world, making sure to carefully write about them in her work. And even though these problems of racial discrimination and sexism are still largely unsolved in today’s world, it is comforting to know that we have work like Yamamoto’s to relate to and to help guide us towards a future light.