Andy Capp and the Survival of the Neediest

When I was a kid, my father, having gone out to pick up milk and the Sunday paper, would bring me back a package of Andy Capp’s Hot Fries. I don’t know how this became a thing between us. I had no particular love for the snack—by the fourth bite you usually couldn’t taste anything because your mouth was on fire—but they were crunchy and fun to eat, the hot-flake powder caking your fingers, and not always easy to find. Plus, the package featured a comic strip on the back: the drunken Andy Capp stumbling home late from the pub or the snooker hall, getting into scrapes or hauled away by constables, and his beleaguered wife, Flo, waiting at home with her hair in a charwoman’s bandana and her arms folded disapprovingly.

It hadn’t registered with me then, but today it seems like a peculiar arrangement of licensing to have an abusive, neglectful, and violent drunk advertise your junk food. The pub-frequenting Capp was presumably chosen by the North Carolina-based Goodmark Foods because the original product line, launched in 1971, included Pub Fries, an homage of sorts to the chips that were a staple of British pub fare. The blander Andy Capp’s Pub Fries have long been discontinued, but Hot Fries are still sold today by ConAgra, which bought Goodmark in 1998.

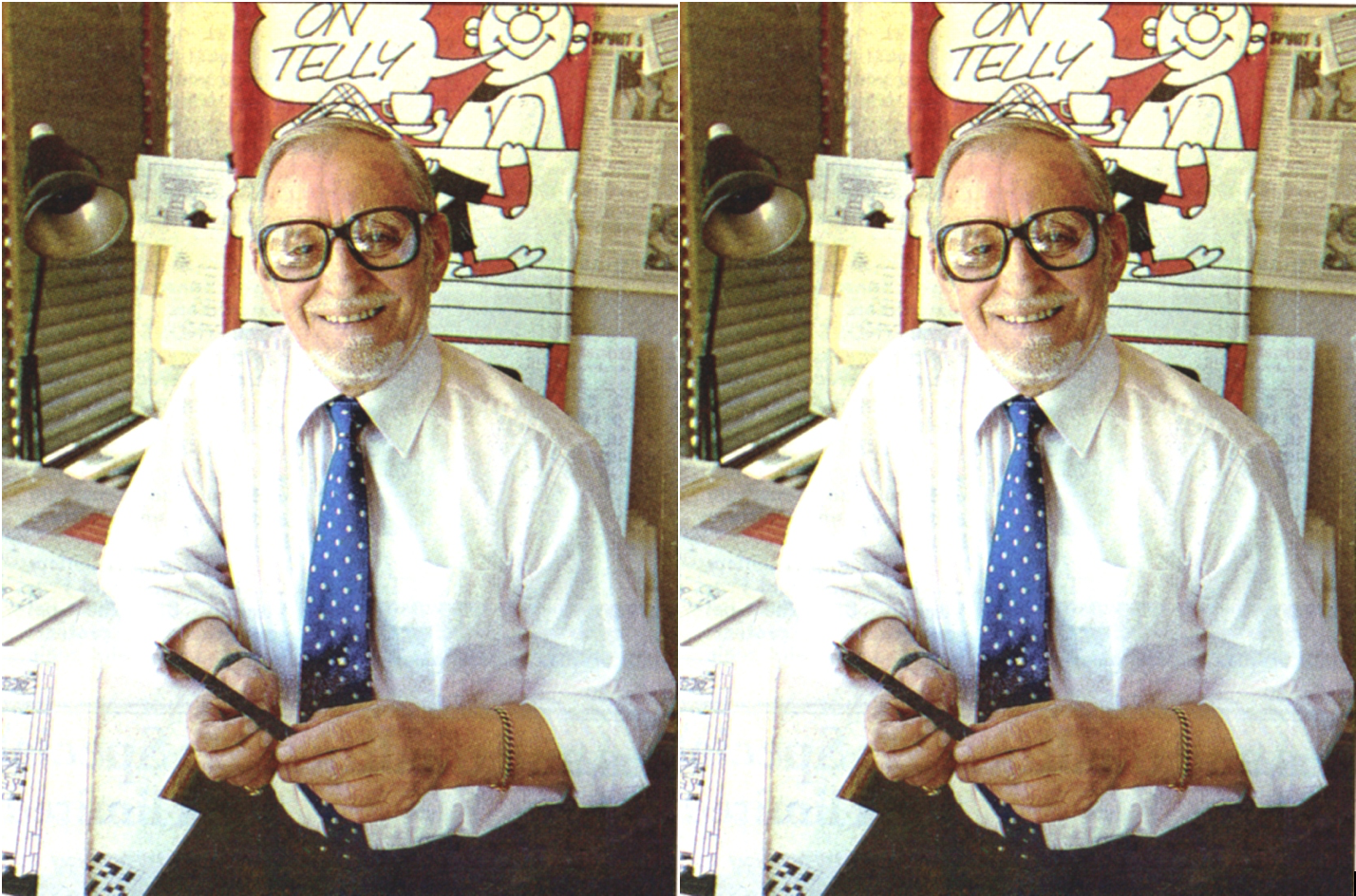

Although the strip was a regular in the Sunday funnies—often appearing on the first page, just below Garfield—there was a lot I didn’t get at the time about Andy Capp, with its taps into poverty, British culture, and domestic abuse. But I liked the nifty way that Reg Smythe drew the panels, with the second panel often stretching, rather than repeating, the scene of the first—a trick that was well suited to the strip’s most common settings: the tavern, the snooker hall, or the townhouse-style layout of the Capps’ home. I liked the way that Flo or Jackie, the bartender, sometimes broke the fourth wall and talked to the reader, or just mugged without comment, keeping us implicit in the gag.

I read these strips in the eighties on the floor of our living room while eating the character’s namesake Hot Fries, brought back by my father—who, upon reflection, might have been out for longer than I, as a kid, had noticed, certainly longer than it took to buy a newspaper. He was never out at obscene hours like Andy. My mother would tease out his whereabouts on those days, somewhat passive-aggressively, by asking who he saw while he was out—knowing that many of his friends and co-workers were regulars at the bar themselves.

Reg Smythe died in 1998, but Andy Capp is still drawn today (by Roger Mahoney, with scripts by Lawrence Goldsmith and Sean Garnett) and published in a dwindling number of newspapers (over 1,500 around the world, according to Creators Syndicate, who distributes it). Andy Capp also has an active verified Twitter account with more than 5,000 followers. I followed the account and the maintainer responded with a DM that I couldn’t help but read in the voice of a somber and slurred Andy: “Thanks for the follow, my friend. Much appreciated.”

It’s fair to argue that Andy Capp, even as it ran alongside more juvenile strips like Garfield and Rugrats, was never meant for children. But children certainly read it, and one wonders how much of their own parents they were likely to recognize in Andy and Flo, in whose marriage moments of grudginess rise to the surface amid what is depicted as devotion. Other long-running strips surrounding couples—Arlo & Janis, Blondie, Sally Forth, For Better or For Worse, even the sour and squabbling Lockhorns—would ground their humor inside the daily domestic perplexity. Andy Capp, in a way thematically resembling Married With Children (a show that my father, tellingly, only watched when my mother wasn’t around, but one of the few that genuinely made him laugh), strikes its one note of unhappiness over and over again, looking back to the nagged reader for recognition, in the same manner of the uncle who winkingly posts misogynistic memes to your Facebook timeline, thinking you, as a younger married man, will understand the same grief.

What I hadn’t realized when I read Andy Capp in the eighties was just how much darker and more explicitly violent the comic had been when it began. It debuted as a single-panel strip in London’s Daily Mirror in August of 1957 and seemed to parallel in its character dynamic—a working-class couple whose best friends are their neighbors—another poorly-aged 1950s staple from across the pond, The Honeymooners—which is also remembered for its casual threats of domestic violence. Smythe’s drawing style then was less flat, viewing the characters at an angle and emphasizing contours, and Andy himself was larger and squash-shaped, as though to bring out his boorishness.

One of the first strips, dated August 20, 1957, shows Andy leaning against the wall of the Capps’ living room with Flo, in her apron, sitting on the floor next to a broken teacup and saucer. “Look at it this way, honey,” Andy says, “I’m a man of few pleasures and one of them ‘appens to be knockin’ yer about!” While Ralph Kramden was threatening with bulging eyes to send Alice to the moon, Andy Capp was laying out Flo without a warning.

As the strip progressed, Smythe took rather superficial pains to equalize the relationship not by eliminating the violence but by complicating and normalizing it as the single panel grew into a full strip. With the flatness of the new layout, the depiction was cartooned (Andy was drawn to appear shorter than Flo) and less about black eyes and whimpers and more about dust clouds—such as Flo levelling Andy with a haymaker that sent him flying back out the door as he stumbled in.

In spite of Smythe’s reticence, abuse and toxicity were an indelible part of the Andy Capp brand, and were very much the angles sold to American readers when the comic was anthologized in paperback collections by Fawcett in the sixties and seventies. On the cover of Watch Your Step, Andy Capp (Fawcett, 1973), Andy is shown tying his shoe while bracing his foot against the rear of Flo, who is on her knees scrubbing the floor. On Andy Capp Sounds Off (Fawcett, 1966), Andy yells at the back of a sobbing Flo: “Of course yer entitled t’ yer opinions, Pet—I just don’t want to ‘ear ‘em, that’s all!” Worse was the tagline provided by Fawcett on the back cover of Sounds Off: “Sound off! Beat your wife! Drink Up! But first buy the book!”

Or take Meet Andy Capp (Fawcett, 1963), whose back cover shows Andy blowing smoke across the table into Flo’s face while they play cards:

Readers all over the world are howling over the daily newspaper antics of this ruffish nogoodnik from Britain who drinks a bit, gambles a bit, knocks his wife about a bit—and doesn’t work—not a bit. Everybody loves him.

Smythe, in later years, expressed regret at depicting what he thought would be a familiar enough currency for his working-class characters to trade in. “It was terribly naïve of me to have done it,” he said of the August 1957 cartoon. “[Andy] was too savage, a proper bully.” Class politics were likely at play. The strip was offered in the hopes of attracting northern readers to the Mirror with a character from their parts (Andy and Flo live in Smythe’s hometown of Hartlepool on the North Sea), but it’s hard not to think there wasn’t also a bit of posturing toward posh Londoners. The message seemed at once boastful and parochial: We don’t need none of your fussiness. This is how we solve problems up here.

Smythe was willing to make other changes. The cigarette that dangled as a rectangular extension of Andy’s lower lip disappeared shortly after Smythe himself quit smoking. But while the material has softened, the dynamic remains: Andy is lazy, shiftless, drawn to his vices, and perpetually granted forgiveness; Flo is an overworked and unappreciated cleaning lady; and Flo’s mother—offering her comments by way of a quote bubble from off-screen—is a nag. The relationship is fraught and abusive, a poisonous domestic partnership presented, with a wink, as familiar. Regardless of whatever opportunities for “revenge” Flo is later given, she is still suffocated in her agency, stomped down in her will, and pinned to some perceived obligation to be there for a man who gives her nothing back. Smythe indicated in an interview that the very name of the character was intended as a comment on his burdensomeness:

What would he be like? Perhaps he would be dead lumber. The type who is a right little handicap to his wife. Handicap! The word handicap gave rise to a really horrible pun. Handicap? Andy Capp! And I had it.

Even holding back on the fisticuffs, or at least saving them for the tavern, Andy Capp is still very much a handicap to Flo—as well as to Jackie and Chalkie (Andy and Flo’s neighbor), and anyone with whom he interacts—and that’s one of the things that makes the strip a painful read today. Andy isn’t so much of a bully anymore as he is exhaustingly needy, and the needy man can’t earn a pint of lovability in this age, not when the needy man is everywhere, crashing international summits and shouting about it on Twitter, making himself loud in comments sections and sucking the air out of conference rooms, forcing the hands of wives and colleagues everywhere to slow down and accommodate his mundanity and pretend he’s a new and interesting spice.

Because there are a finite number of ways to tell a joke about slipping away from responsibility and retreating to a comfort zone, every gag in Andy Capp points to the same desperate spot on the horizon, and it is regrettable that the new management has found only tepid solutions to balance the equation. Flo follows Andy to the pub once in a while now, and plays bingo in the evenings, giving Andy a reason to be pissed off when she hasn’t come home. He complains and insults her when she burns his dinner. The gag is ostensibly about idleness, cheapness, and attraction to vice—the kinds of attributes we overlook in our lovably schlubby brothers-in-law—but even without the fists, there continues to exist in Andy Capp a tacit violence to the role of the domestic citizen, rendered in debts and accommodation, and making heroes out of men who continue to feel owed something from the world even as they give it nothing. Men like Andy need their spaces so as not to be hounded about their responsibilities; women like Flo need theirs to feel safely unconfronted by rage.

Newspaper comics are an art form that speaks to comfort, which has historically allowed them to be exempt from relevance; if anything, their steadfastness against a changing outside world is what makes us come back to them. There is no movement afoot calling for Andy to change his ways. As long as there are Twitter and subscription feeds, strips essentially distribute themselves now, to be followed or unfollowed at will with no ink spilled, and you would think that ephemerality might allow them to see what they can get away with. In the case of Andy Capp, its cultural tone-deafness is not simply a consequence of the strip remaining static to its era. It has followed along with modern allusions: recent strips mention Cristiano Ronaldo, social media, smartphones (Andy doesn’t have one), and FaceTime. Naturally, almost unavoidably, Andy has his protectors, including whoever has written his Wikipedia page. Every strip now feels like a grin delivered around the bar, seeking out allies in pathos, looking for absolution in the manner of everyone does it, friend, lighten up. He is beloved in his hometown of Hartlepool, where a statue of Andy nursing a pint looks out at the North Sea.

Earlier this year, I spotted Andy Capp’s Hot Fries for sale at the Johnny Appleseed rest stop on Route 2 near Leominster, Massachusetts. Someone in Hartlepool must get a few pence from ConAgra for the licensing, but the package doesn’t include the strip on the back anymore. Instead there’s a poorly rendered drawing of Andy lazing on the couch in white socks, munching on his namesake snack and exclaiming with an exuberance that feels at odds with his character, “Life is better with a side of Fries!” Flo is nowhere to be found on the package.

They are still hot on the tongue, still get stuck on your fingers and in your molars. One hundred and forty calories per serving and zero trans fats, and for me, no Proustian callback to lazy Sundays on the living room floor.

Instead, they serve as a reminder of how often our ugliest and most tired characters are casually granted new pathways to reinvent and rebrand themselves, allowed safe distance from darker histories their creators would prefer we forget, while finding pocket networks of loyalty large enough to allow them to maintain a following in a culture that has moved on to demanding more sensitivity to the plight of women from its men and its art. Men like Andy will wait around until we are tired of outrage, then sneak back into the bar knowing they had a seat waiting for them the whole time. Right there next to the snacks.