Disappointment City: Roberto Arlt’s 1930 Trip to Rio de Janeiro

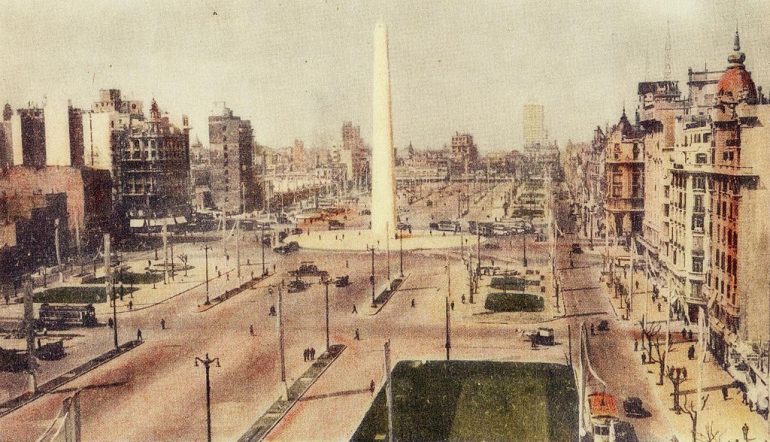

On April 2, 1930, after a short steamship journey up the Atlantic from Buenos Aires, Roberto Arlt arrived in Rio de Janeiro. Dispatched by his editor at the El Mundo tabloid, where he wrote a popular column on everyday life in Buenos Aires, it was the Argentine writer’s first time abroad.

On April 2, 1930, after a short steamship journey up the Atlantic from Buenos Aires, Roberto Arlt arrived in Rio de Janeiro. Dispatched by his editor at the El Mundo tabloid, where he wrote a popular column on everyday life in Buenos Aires, it was the Argentine writer’s first time abroad.

“All I could see,” he wrote of his first glimpse of the Brazilian coastline, “was, at a great distance, a few tall bluish shadows that resembled clouds. And, seasick, I returned to my bunk.”

But like a painter who begins a massive canvas with a few tentative dabs of paint, Arlt emerges from his cabin two hours later, ready to unleash an enormous freight of description:

“A semicircle of mountains, which appear spectral, as weightless as blue aluminum, are crested delicately with a green lining…further down, domes of blue porcelain, red dice, white cubes: Rio de Janeiro! […] The city descends and rises, a street, here in the depths, then, 100 meters above, another; an alley, a pothole, glades and grass-green hillocks, with reddish cavities, looking out onto an abyss… Little rectangular windows; a forest of tamarinds, feather duster trees, palm trees, and next to that staircases of cobblestones, open footpaths of chocolate-colored dirt, and the perfectly straight Avenida de Río Branco…its buildings painted pink, painted cacao, painted brick red, green awnings, shadowy passageways, trees on the sidewalk, streets drenched in a golden sun…”

My own first image of Rio de Janeiro was somewhat less prosaic. One morning in June of 2013, I arrived by bus from São Paulo, the Brazilian industrial capital, where I was working as an intern at a global newswire—my first job out of college. When I awoke outside Rio’s bus terminal in the run-down port zone, the first thing I saw was a man clad in grimy flip-flops and fluorescent swim-trunks walking alongside a dilapidated, graffitied wall. This man, and his surroundings, made for a jarring contrast from the city I thought awaited me. I had come, like I suspect many visitors do, expecting the postcard view of the bay, of the beaches, from the first moment of my arrival.

It was only when I returned to Rio three years later and read Arlt for the first time that I began to grasp that the distance between expectation and reality, between hope and disappointment, animates and haunts the experience of the outsider to a foreign country.

*

When I spontaneously decided to join my partner, an American journalist, in Rio in March of 2016, I knew very little about the city beyond what I had seen on that first trip. Though we didn’t end up dating until years later, I had actually met my partner—who has lived in Rio off and on since 2012—in Rio in 2013. At the time, the country was convulsed with massive street protests against corruption: the night we met, we narrowly avoided being teargassed after a roving group of teen anarchists—followed shortly thereafter by riot police—ran through the neighborhood where we were having dinner.

In 2015, I quit my job with the newswire in New York without a backup plan; I was desperate for an adventure and low on cash. Though we had only been dating for a few months, my partner agreed to split an apartment with me through the end of the Olympics, which would be hosted in 2016 in Rio. A friend who had never been to Brazil, sensing my nervousness ahead of the move, gave me a recently unearthed collection of Arlt’s travel notes from Rio as a gift.

Arlt was born in Buenos Aires in 1900 to recently arrived and near-destitute European immigrants. An avid reader as a child, who consumed Dostoyevsky and adventure novels with equal relish, he left school and then home by sixteen, seeking his fortune in a series of failed inventions and odd jobs—(“What damned job haven’t I done?”)—all while working on essays, stories and, later on, plays. His first novel, El Jugete Rabioso (The Mad Toy) was published in 1926; by 1927, journalism had become his main source of income. The next year, he was hired by El Mundo, where he began to write his Buenos Aires columns, which were entitled aguafuertes, or etchings, after the printmaking process that uses chemicals to burn an image onto a metal plate. His aguafuertes porteñas are brief, caustic commentaries on a city undergoing enormous change, both technological and political; they eschew politeness or high-mindedness, preferring instead to replicate the kinds of conversations happening among workers around newsstands. Their enduring power, however, stems from the fact that Arlt writes himself into them as the anti-hero of a narrative of his own construction. The aguafuertes are conversational; they are written as though the latest installment in a long-running conversation between reader and writer. Arlt is keenly aware of his audience’s (often lowbrow, though witty) desires and tastes, and is unafraid to acknowledge them, frequently appealing directly to them to make a point.

Arlt’s voice in the aguafuertes is very much in keeping with that of his fictional oeuvre. His novels—the best of which, Los Siete Locos (The Seven Madmen), was republished by New York Review Books in English in 2015—all feature overeducated, underemployed men as their protagonists. The children of immigrants, they are resentful of a world that has kept prosperity and popularity just out of reach. Revolutionary ideas and plots provide much of the fuel for what passes as plot. His prose is brusque, forceful, simple—and often bitterly funny. (Imagine a Bukowski where alcohol and sex are replaced by Nietzsche and astrology.) Arlt is, in a sense, the anti-Borges: a pugilistic provincial who reveled in colloquialism, slang and conspiracy.

The trip to Rio came at an important moment for Arlt. Los Siete Locos, his second novel, had come out just a few months before the trip, while the success of his aguafuertes porteñas had garnered him an unimaginably wide readership in his beloved home city. So when his editor dispatched him to Uruguay and Brazil, Arlt responded with glee. “To get to know and to write about the lives and the strange people of the Republics of northern South America! Tell me, frankly, isn’t that beautiful, like winning the lottery?”

Every writer is an exemplar of her time and place; none more so than a travel writer. One of the delights of reading the aguafuertes cariocas in 2016 came from Arlt’s blithe, and total, identification with himself. He is a comically bad guide to a foreign city, the very inverse of what a twenty-first century foreign correspondent is trained to be. He is quick in his judgments, stubbornly parochial and, perhaps strangest of all, hardly interested in meeting or speaking with any Cariocas, as residents of Rio are known, after the underground stream that runs from beneath Christ the Redeemer’s feet on Corcovado peak into Guanabara Bay. Instead, he observes them from street corners, cafés, movie theaters, and newsstands, reporting back to his readers with broad declarative statements on the Brazilian psyche. (Day one: “Defining Rio de Janeiro forever I would say: a city of decent people. A city of well-born people. Rich and poor.”)

Arlt’s insistence on identifying with his reading audience, his refusal to blend in or ask the right questions, as well as his stated claim to avoid the wealthy and powerful and commune solely with people on the margins intrigued me. In my training as a journalist, I was taught to be unobtrusive, to ask open-ended questions, to listen—mostly to the wealthy and the powerful, the “market movers”—and resist the urge to jump in with my own opinion. Reading Arlt, who takes the opposite tack, gave me a private shiver of illicit delight.

Yet another strange pleasure of reading Arlt in 2016 was in the endless enumerations of how the city has changed over the years. Arising early on his first day, for example, Arlt is shocked to note that bread and milk deliveries are simply left on doorsteps without fear of being stolen; that trolley attendants wait patiently for commuters to pay their fare; and that women walk freely throughout the city, even at night.

“I enter another cafe,” he writes. “A girl, alone, drinks her chocolate soda and nobody bothers her. I am the only person who stares at her; that is to say, I’m the only rude person here.”

I too was shocked at the description, but only because in the eight-and-a-half decades since his visit, some of the neighborhoods he describes as bucolic have been ravaged by deindustrialization, drugs, and decay. The federal government moved to Brasília—a city built expressly for the purpose of serving as the nation’s capital—in 1960; many of the nation’s banks departed for industry-heavy São Paulo shortly thereafter. In the succeeding generations, the city’s wealthy have built new enclaves for themselves farther and farther from the old city center where Arlt roamed. (My partner, who has done extensive reporting on sexual harassment, snorted at the notion that a man would be able to tell whether or not a woman were being leered at by other men in a café.)

Certain experiences, I found, could still be shared with Arlt. The best way to understand Rio, for example, is still to see it from above. Whereas São Paulo makes a sort of pure sense as a city—it is city in every direction, all the way down—Rio makes no sense at all. It is bisected, diverted, limited, interrupted by a wild array of ocean, bay, and forested mountains of solid granite rock. The true ingenious response to the city’s arduous geography is not that of the few, skinny, inadequate, overloaded tunnels that desperately try to weave a coherent fabric out of the city, but rather that of the favelas, which climb the hills in nearly every neighborhood, giving the city a reassuring continuity. Nearly a quarter of all Cariocas live in its favelas and its distant suburbs, and they provide the city with its employees as well as with its autochthonous culture. The favelas are the inverse of the glazed wealth of Ipanema and Barra da Tijuca, where the Olympics were held; they loom above the beaches and the wealthy; their physical presence a continual, constant reminder of the sources both of the city’s anxieties and of its pleasures. Many Cariocas do asfalto fear the favelados just as they depend upon them, not only in their daily life (nannies, gardeners, cooks, drivers) but also as the very source of Brazilian-ness for export.

My first view of the city from above came at the end of an arduous hike up the Morro Dois Irmãos, a set of twinned granite peaks that jut out between the Vidigal and Rocinha favelas, which offer a panoramic view of the Atlantic coastline, the Guanabara Bay, and all the many neighborhoods that lay in between. Perhaps it was my exhaustion and dehydration, but on that first hike I managed to find the view somewhat disappointing, as though I were looking out at an enlarged postcard. Rio is almost unimaginably beautiful, a fact I am (painfully) reminded of whenever I open Instagram these days. Yet while seeing it from above helps one understand the unlikely layout of the city, it minimizes that which makes Rio, Rio—the people who fill those same neighborhoods that seem so picture-perfect from above.

Returning home that evening, I discovered that Arlt, too, found his first view of the city from above—his was from the famous Pão de Açucar, or Sugarloaf, the huge granite rock that juts out from Guanabara Bay—somewhat lacking, too. Overwhelmed by the city’s confounding shape, he closes his eyes. Opening them again—and switching to the third-person—he finds that

Suddenly the city has disappeared before his eyes. He shivers from the cold. He looks around. Everything is totally grey. The Sugarloaf has been enveloped in a passing cloud.

*

The promise offered by the return of Brazilian democracy in 1988—after two decades of a military dictatorship—seemed to be fulfilled in 2003 by a short metalworker missing a pinky finger. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s rise from poverty to the presidency carried with it an implicit promise—made explicit on the campaign trail—that Brazil’s long-ignored poor and working classes would gain recognition and opportunities for the first time in the nation’s history.

Under his government, income inequality narrowed dramatically as some forty million Brazilians moved into the middle class; scholarships and affirmative action policies made college a realistic option for poor and black Brazilians for the first time. The crime rate continued to tick downward, while the economy boomed.

The apotheosis of this period of hope came during Lula’s second term, when Brazil was awarded the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics—which were to be hosted in Rio. In Rio, the promise of the mega-events spurred enormous plans. The long-abandoned port zone and city center were to undergo a beautification project; the city’s public transit system was to be expanded and improved; the iconic—and heavily polluted—Guanabara Bay would be cleaned up; and, perhaps most consequentially, an enormous investment program was developed for the favelas. Apartments would be built; sewer lines and public utilities would be installed; and sporadic military-style invasions by police (with attendant eye-popping casualties) would be supplanted by the UPP, a “pacifying” police force whose continual presence and special training would dislodge the gangs and provide the basis for the other improvement projects.

But by 2013, the promise offered by the mega-events was starting to curdle. When I first arrived in the country in June, a series of enormous protests had just started to unfold on the streets of Rio and São Paulo. (Hence that first night of tear gas.) Triggered initially by an increase in bus fares, the protests soon came to cover a host of grievances felt by many Brazilians, including shoddy roads, hospitals, and schools. (One memorable set of signs demanded “FIFA-quality schools” for Brazilians.) Against the backdrop of final preparations for the World Cup and Olympics—not to mention the beginnings of an economic downturn—many Brazilians were starting to feel that the promise of the preceding decade was not being fulfilled. Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, lacked his preternatural charisma and initially struggled to find a response to the protests.

Still, there was something undeniably joyous in the scenes that played out on the streets that June. The protests were inclusive, as Brazilians from across the political spectrum and generations came out to air their grievances and propose their lists of demands. On one of my first nights in São Paulo, I stood on a concrete barrier at the intersection of two major avenues and watched for at least twenty minutes as the crowd filed past; later, I spoke to a friend who passed a major landmark a full hour after I did. The old hands in the newsroom said that they were the biggest protests since 1991, when a protest movement forced a president out of office.

The fullness of the discontent paradoxically contained, I thought at the time, the possibility for another step forward for the country. Millions of people who had been desperately poor could now afford cars and televisions, but what came next?

I left São Paulo that August with the sensation that I had been witness to a major expression of political renewal. In college, I spent a few weeks visiting the Occupy Wall Street encampment at Zuccotti Park in Manhattan. While I recognized in the Brazilian protests a similar wide-ranging (or perhaps aimless) sense of frustration as in the New York movement, the Brazilian protests were vast. Here, I thought, was a genuine expression of a popular movement.

But by the time I returned to Brazil in 2016, the picture looked notably different. An enormous corruption investigation, begun in 2014, proved what many of the protestors had long believed: the political and business elite were hopelessly corrupt, focused solely on enriching themselves. The World Cup had been a costly boondoggle, empty stadiums rotting or, in one case, being used as a parking lot for buses. (Brazil’s 7–1 loss to Germany in the semifinals certainly didn’t ease the pain.) A painful recession had revealed the fact that many people had financed their new lifestyles on credit; unemployment and crime began to rise.

Moreover, the country’s right-wing had taken the energy of the 2013 protests and sharpened them into a demand to oust Rousseff, who had barely eked out a reelection victory in 2014. Not long after we arrived, my partner and I attended a rally where men dressed in military fatigues, astride a Humvee, held up signs demanding a return of the military government—a refrain heard more and more often in Brazil these days. The protestors carried signs depicting Lula and Rousseff as stripes-wearing prison inmates; they hailed Sérgio Moro, the federal judge leading the corruption investigation, as a strongman savior destined to wrest power from the PT. Meanwhile, the “opposition”—the government’s supporters—organized anemic rallies in response, full of left-wing slogans and banners that felt discordant with the reality of a decade of PT rule.

In this disappointment—that of the Brazilians I had come to know well, as well as my own—I found that Arlt, too, had walked before me, though for decidedly different reasons. By day twenty of his trip, Arlt begins to feel some apprehension about the genial placidity of the Cariocas (“sweet, tame, calm”) he encounters: what, he asks, is a man like himself doing in such an “honest and trusting” city? Meeting writers and other “important” personalities doesn’t interest him, nor does the prospect of visiting historical monuments: “Brazil’s beauties leave me dry.”

Arlt finds himself retreating into a reluctant nationalism, finding in casually observed Carioca habits a reinforcement of the primacy of his own city. Cariocas go to bed early, he complains; they do not linger in cafés or organize underground political activities. They go to work, then they go to bed. In one of his last columns, Arlt is horrified to learn that slavery had been abolished in Brazil only as recently as 1888, meaning that a significant proportion of the black people he saw walking the streets of Rio—whom he had previously dismissed with casual slurs—were either born slaves or born of them. Suddenly, the opportunity to fulfill his intention, stated in his first column, to “mix with and live among the people of the underworld” presents itself. Instead, he turns away:

I still haven’t decided to interview an ex-slave. I don’t know. It terrifies me to enter the “country of fear and punishment.” What [a friend] told me sounds like the plot of novels…I prefer to believe that [what he told me] is a story that took place in a fantasy-land. I think that’s better.

Arlt’s failure to fulfill the task he set out for himself, to fully immerse himself in a foreign society, leads him to the conclusion that he would have been better off staying home, in what he calls his “own slum.” (“It wouldn’t be as hard for me to find subjects to cover there as it is here…”) He is put out of his misery when a note arrives informing him that Los Siete Locos has won third place in a local literary contest in Buenos Aires. A week later, he is on a hydroplane heading back home.

*

In June, just weeks after Rousseff was suspended from office pending a vote on impeachment and a month before the opening ceremonies of the Olympics, I had a chance to visit the Olympic park in Barra da Tijuca, a heavily developed strip of gated condominiums and highways in the city’s southwestern quadrant. By then, the corps of foreign journalists—many of whom had moved to Brazil at the height of the period of promise—had largely joined the public in turning against the Olympics, seeing in them the vast profits developers and politicians had made, as well as nearly all the unfulfilled reforms and improvements to the city. There was a palpable sense of disappointment among the city’s outsiders. Many of my partner’s and my non-Brazilian friends were leaving the country after the Olympics; Rousseff’s final ouster, in August, was for many foreign journalists the coda to the journey that had brought them to Brazil in the late 2000s.

Walking through the empty park was an uncanny experience. The spaces between venues were vast barren stretches of concrete and brick; the venues themselves felt like movie sets on a soundstage—best observed from a distance. One of the stadiums, a Rio 2016 press officer explained without much enthusiasm, would eventually be converted into four public schools—yet another dubious claim that fell by the wayside.

Brazil’s long status in the foreign imagination as the “country of the future”—as Stefan Zweig and countless others have called it—contains within itself the seeds of disappointment. A nation that is all potential must inevitably lead to unfulfilled expectations.

Near the end of his journey, at the height of his annoyance with Rio, Arlt declares that “landscapes without humans bore me. Cities without problems, without zeal, cities with men without psychological problems, without worries, flatten me.” In Rio, he writes, “those who live poorly don’t realize it, they accept their condition.”

I laughed the first time I read those words. Today, Rio is nothing if not a city wracked by worries and social strife. Yet Arlt’s experience in Rio, no matter how different the city he had visited was from the one I inhabited, made me appreciate a certain resonance between his flamboyant disappointment and the one shared by myself and the others who thought we had found in Brazil the promised future.

As I reread those words, I thought of how Arlt and I—two outsiders pinning their hopes and frustrations onto a city not their own—had ultimately inverted experiences while in Rio: Arlt was full of excitement upon his arrival, and left disappointed with what he found. By getting to know the city during a moment of grand disappointment, meanwhile, I had been forced to find a way to appreciate the city on its own terms, freed from (at least some of) the baggage of expectation that so many outsiders had placed onto Brazil. Certainly Arlt, with his chauvinism and his intolerance, is a terrible travel companion. Yet like the mad king’s truth-telling court jester, his strange little book helped me better understand the peculiar stake many of us take in countries that are not our own.

At any rate, Arlt soon enough realized that the deepest disappointments often await us at home: not long after his return to Buenos Aires, a military dictatorship overthrew Hipólito Yrigoyen, Argentina’s first democratically elected president. After learning that the staff of the newspaper La Fronda had been arrested, Arlt’s response—under the watchful eye of his terrified editor—was characteristically sly: “The tiring monotony of daily routines has disappeared. Nobody knows anything about anything, and that’s enough to enliven life.”