Fiction Responding to Fiction: Henry James and John Cheever

The Fiction Responding to Fiction series considers the influence that a short story has on another writer; all entries can be found here.

Henry James published “The Jolly Corner” in 1908. One of James’s most anthologized stories, “The Jolly Corner” is a ghost story with multiple interpretations. Indeed, there is little agreement over whether the protagonist is alive or dead at the end of the story. A little over fifty years later, John Cheever published “The Seaside Houses” in the New Yorker. While Cheever pays homage to James in both the themes of change and loss, as well as in the construction of his story, he uses the differences between the two stories to critique the mid-century American way of life.

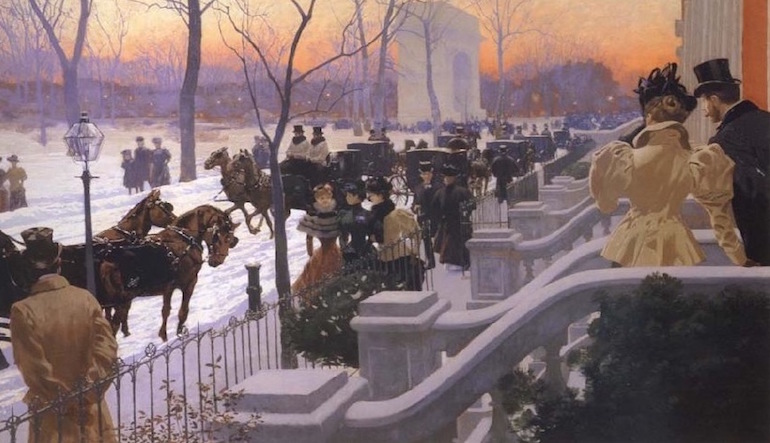

In James’s story, Spencer Brydon returns to New York from Europe, after an absence of thirty-three years. (Whenever the number thirty-three is pointedly used, I can’t help but wonder if it’s a nod to the length of Christ’s life and, in this case, the resurrection.) Brydon has been living off his family’s fortune and now, following their deaths, he has returned to oversee his primary inheritance: two buildings in Manhattan. One is being turned into apartments—surely a comment by James on the rapid change in Manhattan at the turn of the century—and the other is left empty. Brydon shows his old friend Alice Staverton both buildings, and they talk about the unlived life: what would Brydon’s life have looked like had he stayed in New York all those years? Until now, it seems, Brydon has rarely questioned his life choices.

Brydon visits the empty house often and becomes convinced that his alter ego—the man who stayed in New York—inhabits the house. One night he stays and tracks the man down, finally coming face-to-face with this ghost as he comes to a realization about his own lived life: “That meaning, at last, while he gaped, it offered him; for he could but gape at his other self in this other anguish, gape as a proof that he, standing there for the achieved, the enjoyed, the triumphant life, couldn’t be faced in his triumph.” It becomes difficult for us to parse James’s language, to understand which is the self and which is the other. The two seem to have elided into one.

The third act of James’s story has Brydon’s friend Alice finding him in the house after this incident. His head in her lap, he tells her about his encounter, and she tells him that, once again, she has seen his alter ego in her dreams. It is not clear, here, whether Brydon is in fact dead or whether he is still alive, whether this encounter will help him to live a more realized life. The story ends with Alice supporting him—as she has done throughout—and forgiving him of his past transgressions.

Cheever sets up the connection to James’s story at the start of “The Seaside Houses”:

Each year, we rent a house at the edge of the sea and drive there in the first of the summer—with the dog and cat, the children, and the cook—arriving at a strange place a little before dark. The journey to the sea has its ceremonious excitements, it has gone on for so many years now, and there is the sense that we are, as in our dreams we have always known ourselves to be, migrants and wanderers—travelers, at least, with a traveler’s acuteness of feeling.

Many of the elements of James’s story are here: a journey; a house in the night; a knowledge of the self in one’s dreams. But Cheever’s insistence that the collective voice of this opening section—written in the present tense—consists of restless wanderers immediately sets a different course for this story. Whereas Brydon didn’t stay at home, others in his family did. The post-war culture, Cheever seems to be saying, has lost an attachment to place; a generation of Brydons has emerged.

While the architecture of the stories are similar—three sections each, with a clear narrative arc marking the beginning, middle, and end—the structures within the stories are vastly different. Brydon owns these houses in New York; they constitute part of his legacy. It is deliberate and telling that Brydon owns two properties: just as he believes that he has an alter ego, the houses also function as duplicates. One is being divided up into smaller spaces while the other is devoid of almost everything that Brydon remembers from his youth, with the exception of a few pieces of furniture. It functions as a place for remembrance and for the start, perhaps, of self-reflection.

On the other hand, Cheever’s protagonist Ogden is a renter. A privileged white renter, to be sure, who travels with a cook and thinks nothing of flying back to New York for a day or two, but a renter, nonetheless. He does not own these properties, he merely borrows them, slipping into the owners’ lives for a month or so. He snoops through their things, listens to gossip from neighbors, and tries on a different house each year: “the wooden castle with a tower, the pile, the Staffordshire cottage covered with roses, and the Southern mansion.” Nothing is fixed, nothing is constant. Everything is impermanent.

At one point, Ogden has a confused dream that recalls the objects in the house but also his identification as a traveler. When he wakes, he thinks that “it seemed that I had dreamed one of Mr. Greenwood’s dreams.” So not only does he read the owner’s books and drink out of his glasses, but he also tries on his unconscious life. Ogden is restless and unhappy, but he, unlike Brydon, does not self-reflect. Rather, when the going gets tough, he leaves, in a way that only Cheever could pull off:

“Oh, God, you bore me this morning,” my wife said.

“I’ve been bored for the last six years,” I said.

I took a cab to the airport and an afternoon plane back to the city. We had been married twelve years and had been lovers for two years before our marriage, making a total of fourteen years in all that we had been together, and I never saw her again.

Cheever finishes his story with a flash forward—again, as in the opening, written in the present tense. Ogden is in another seaside house, but he now has a different wife. Whereas the altercation with the first wife that led to his leaving was that he had misplaced his swim trunks, now his second (or perhaps third or fourth) wife asks him to find her glasses. He is now, it seems, the one without the power, and still searching for the lost objects. The story concludes as Ogden finally asks questions of himself and allows himself to feel the losses that he has created, to recall and echo a moment from earlier in the story: “In the middle of the night, the porch door flies open, but my first, my gentle wife is not there to ask, ‘Why have they come back? What have they lost?’”