Review: I KNOW YOUR KIND by William Brewer

I Know Your Kind

I Know Your Kind

William Brewer

Milkweed Editions; Sept 2017

77 pp; $16

Buy: paperback

Reviewed by Mike Good

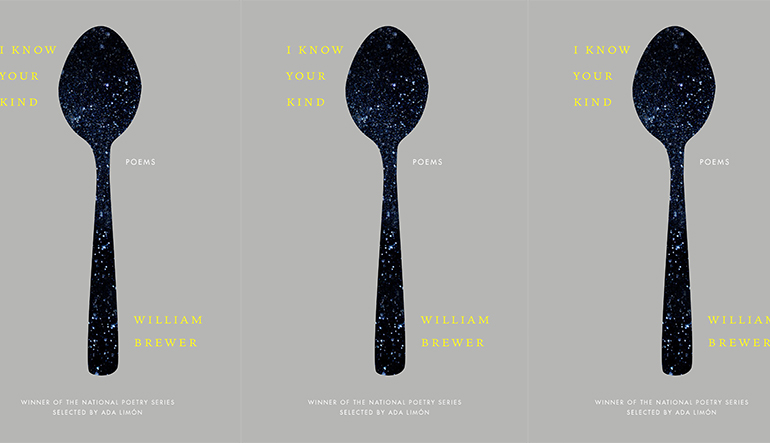

A winner of the National Poetry Series selected by Ada Limón, William Brewer’s debut full-length collection plunges into the depths America’s opioid epidemic in the town of Oceana, West Virginia. At the center of the book’s cover lies the silhouette of a spoon; within the silhouette are the stars of the night sky. The cover image recalls one of many standout poems in this stunning collection, “To The Addict Who Mugged Me,” where Brewer wryly attempts to forgive the assailant in the aftermath of being assaulted, writing “Wherever you are// with your stamp bag of winter,/your entire universe boiling/ in the breast of a spoon.” A stamp bag is a small stamp-sized bag containing heroin, presumably stolen from the speaker. With scars across its pages, I Know Your Kind conveys the pervasive shadow the opioid epidemic casts across Oceana—and, by extension, towns like Oceana—in a way that statistics, figures, and journalism cannot.

The first epigraph offers the source of the book’s title: a line from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, priming the volume for extended scenes of desolation. If violence colors the desert landscape in McCarthy’s book, causing characters to lose their humanity, addiction and the attempts to escape dependence colors Appalachia’s fields, mountains, and people with acute tragedy. The second epigraph explains Oceana’s appellation, “Oxyana,” due to the town’s high concentration of OxyContin abuse. Upon reading this book, one cannot help but reckon with both the brute impact of the epidemic on users in addition to the less-seen effect on extended family, loved ones, friends, and throughout communities.

Numerous lines suggest addiction’s defamiliarizing and dehumanizing effects. What is so remarkable about this poet is his ability play a lead role in each scene while describing the action with unattached observation. For instance, in “Naloxone” (Naloxone is a drug administered in the event of an opioid overdose), Brewer writes, “Someone//found me in a coffee shop bathroom/after I’d overdone it//and carried me like a feed sack/to the curb.” The lead actor both becomes scenery and describes himself disappearing from the stage. This simile is one example of Brewer’s figurative language that clings to the reader long after words are spent.

Structurally, the book contains no sections, forming a continuous stream of lyric and narrative. Often, lyrical poems address the landscape, anchoring the personal to a larger context and speaking in a collective “we,” whereas the speaker of the narrative poems appears to be a close stand-in to Brewer. Rather than sequencing series of poems consecutively, linked poems such as “Icaraus in Oxyana” and “Daedulus in Oxyana” offer distant echoes a dozen pages apart. Forgoing narrative and formal ordering helps arrest the notion that a straight path exists between dependence and sobriety. Instead, an image or a phrase frequently connects poems. Brewer also sprinkles certain words throughout the collection, including “gravity,” “light,” “gold,” “dark” “night,” “bone,” and “brass,” adding aesthetic cohesion and a Neolithic backdrop for poems to unfold.

In many ways, I Know Your Kind recalls Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky With Exit Wounds, in-part due to the way poems appear on the page and due to each poet’s particular contemporization of Greek mythology. In Brewer’s best constructions, his lines have an ability to set and to shift like striated sediments on a cliff face. For instance, the first three lines of the collection begin, “None of it was ever ours: the Alleghenies,/ the fog-strangled mornings of March,/cicadas fucking to death on the sidewalks.” The first line establishes point of view while evoking a sprawling grandiosity to the landscape and connecting the speaker to a regional narrative. The second line has the feel of classic poetry with “fog-strangled mornings” a distant cousin of Homer’s “wine-dark sea.” The third line wrenches us from the cosmic, pulling us back to the earth, with the visceral and vernacular.

Rather than offering epiphanies and conversions, the politics of Brewer’s poetry reflect an overwhelming sense that a great injustice was inflicted upon land and people. Occasionally, Brewer casts blame on corporations and politicians for creating Oceana’s environment. However, they take a backseat to the people within poems who never lose volition, and the poet condescends to neither reader nor subject. Instead the book demonstrates awareness that its audience is comprised of outsiders, earning lines like, “…if most people/ can’t conceive of the earth wanting something so badly/ that it’ll throw away life once it gets it,// how can I expect them to believe in my suffering?” Balancing difficult material with refined style, I Know Your Kind gives voice to a submerged perspective and creates a startling experience.