Conversation in The Affirmations

My first reading of Luke Hathaway’s The Affirmations happened on a train stirring eastward through Pennsylvania on a day that was spring by calendar but not in sight, the fields still sere, the sunlight thin. In the quiet car, the living hum of bodies and tasks carried on around me, each of us experiencing a communal kind of solitude, while I sat in the deep winter of the collection’s second poem. Hathaway writes, “Yesterday the river ice, till now page-blank, was annotated / by coyotes. I followed their new year letters down along the / west side of the island[.]” These lines’ playfulness is sheer delight. I was also taken by the impulse toward collaboration in the construction of their image: the speaker stands open to envisioning such a text (in and through the movement of the coyotes) and brings curiosity to it. This feels different from simple visual eavesdropping; the coyotes and the speaker are engaged in an act of creation, even though each is separate from the other.

To return, a moment, to the train: The Affirmations is a very good book for reading in a quiet place—the poems demand attention, both with their often austere beauty and their rich and challenging depth of reference—but these poems contain so much conversation—sometimes with people present and absent, sometimes with the self, very often with other texts—that it would feel strange to read the book in absolute isolation.

In that second poem, Hathaway takes up the metaphor of conversation directly. Writing in emulation of W. H. Auden’s long “New Year Letter” to a friend, Hathaway writes a New Year letter of his own. In a contextualizing preface to this multipart poem that acknowledges references to “other spirits, familiar and unfamiliar” to the reader, he writes, “but for the most part / they are like the guests at a dinner party: one doesn’t need to / know their names (I hope) in order to enjoy the conversation.” This is the intimate artifice of the letter as a form. Readers here are less in the position of voyeur—separate, secret—and situated more as new friends on the edge of a meeting of old friends. Approaching the work in good faith, one listens to learn, rather than to interject or reframe. Though the reader may have no personal or intellectual tie to the late poet Richard Outram, mourned here, one listens to bear witness and give space for grief. The richness of the relationship between Outram and the speaker reveals itself in glimpses—anachronistic spellings, full of tender learning, a poem ended by a Welsh carol—but those glimpses don’t give the reader the experience of the friendship, don’t fit that loss into the reader. Something remains private and personal, and that the poem allows for that distance makes it all the more affecting, all the more true.

The depth of references offers opportunities for entry and distance alike. Ranging freely across centuries of works, sacred and secular, Hathaway’s book, published last week, is as deftly conversant with John Donne as with Auden, as expert in its command of music, metrical and lexical as the maritime landscape. “Ballad,” for example, bears a subtitle honoring David Thomson, author of The People of the Sea: A Journey in Search of the Seal Legend (2002), an exploration of selkie folklore, and borrows a refrain from traditional songs. Subsequent poems, like “Deus est sphaera cujus centrum ubique circumfrentia nullibi” and “Caeneus,” invoke Greek mythology, and all speak of the transformative power of the sea. Significantly, though, “Caeneus” in particular presents a new imagining. Caeneus, in myth, is transformed from a woman into a man by Poseidon; the reason for the transformation varies according to the version. In Ovid, Caeneus demands to become a man after Poseidon rapes her. In Hathaway’s poem, a spare twelve lines, Poseidon exists only by allusion and implication; knowing Caeneus’s name and the myth anchors the “him” within that conversation as the god of the sea. Another reader might hold fast more simply to the longing in “Ballad” and “Caeneus,” made more intense by threads of uncertainty as to who, exactly, is begging for change: “could have been her voice it / could have been the waves though.” The metaphorical possibilities gather strength as the collection progresses, their resonances accumulating, John Donne’s pain and passion battering Hathaway’s “Nocturnall” even as Hathaway speaks to Donne’s anxiety in a voice that does not need Donne in order to soothe: “Sit down, / wait: with him. / For the sun.”

“A Poor Passion,” a new consideration of Bach’s Johannes-Passion, stands as the centerpiece of the collection. The libretto also has a prose preface, in which Hathaway writes, “in the hands of power, stories become plagues: they are wielded as doctrine, and used to repress, to silence, to assimilate and destroy. But I don’t think stories are happy there, in the hands of power; I think the holy spirit, the inspiring voice, deserts stories so conscripted. It goes back to the root of breath, the sacred fire, to inspire another teller, another version—to enter the world again, as life and light.” The object, then, of The Affirmations, is not simply reifying what has come before, but challenging, re-imagining, and reclaiming what has been made into a tool of oppression.

Even—or especially—the very first poem in the collection, “A Nativity,” takes up that work. The title itself is an invitation to association: a nativity conjures, for many, the nativity—Mary, Joseph, the infant Jesus, the attendant shepherds, and so on—and in Hathaway’s collection, a conversation with faith and sacred texts and sacred music as much as a conversation with transness, such association is encouraged. “A Nativity,” however, is oblique; what is evoked by the title manifests no more concretely in the body of the poem. The opening lines bring a reader to a place in which apple trees carry only the faintest inevitable whiff of Edenic metaphor; they serve much more richly as a landscape to travel through:

Past contorted orchard apples,

quickly now, toward where the road

bends sharply to the north, the light

increasing as I go so that

I can’t be sure which one of us

illuminates the fence[.]

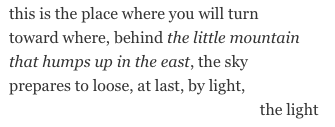

“A Nativity” is a poem of movement and arrival. The intimate journey of the speaker and the unidentified you brings reader and poem to a moment of transformation:

The delightful delicacy of “loose” (as opposed to “lose”) is a harbinger of many such moments to come throughout the collection. Hathaway’s erudite sensibilities offer up play while creating images of buoyant and understated beauty. The poem’s end is a dawning, a place of becoming. As the opening frame of a collection of poems in which Christian faith and gender transition are both celebrated as integral to the speaker’s experience, “A Nativity” feels foundational.

The Affirmations is a collection of poems that could invite many direct descriptions like the one in the previous sentence, but in assigning such a description, I do fear flattening the poems into a single thing, about one thing, voiced in one voice. The mysteries of Christianity are, of course, wholly present here, but so, too, is the reminder that Christianity is a religion anchored much in books. These poems are filled by the author with the echoes of other authors—and I will continue to be doggedly charmed by those scribing coyotes—which becomes an act of generosity and connection. In the act of reading a collection of poems also so devoted to reading (texts, situations, possibilities), a reader makes with The Affirmations a communitas, a term often applied to those who form informal groups as they progress in pilgrimage. The Affirmations makes a journey of shaping not only poems specifically focused on trans identity but also poems moving toward that titular, encompassing yes. The final poem, “Ite, Missa Est,” moves thus: at the same time the speaker is transitioning, a friend is leaving the priesthood, and both are stepping out on new paths. “Christopher,” the poem asks, “when the Atlantic rose against us / did we grapple at the net— / or did we let ourselves be swallowed, let / ourselves be loved like that?” There are tragic versions of these stories—queer and trans people ostracized from their communities, made subject to horrifying violence physical and otherwise—but the iterations here are not tragic. Without ignoring the world and its realities, the poem leans in its fourth section, as Hathaway emphasized earlier, toward light and life:

I wake to gulls and in their cries

I hear no trembling for the fact

of death in these home waters. No.

They scream for life. That urchin wrenched

from intertidal privacies and gut-

smashed on the rock: they don’t

avert their gimlet eyes from that.

No, Sir. They lift it up.

“Ite, Missa Est,” a poem in six parts, concludes in a loose sonnet, its four-footed lines and musical rhyme bringing ease and comfort to stanzas already choosing to end on a note of reassurance: the two central figures of the poem, despite great changes, will remain legible to each other. Such is faith, and love, and for all that there are mysteries therein, here are constants too.