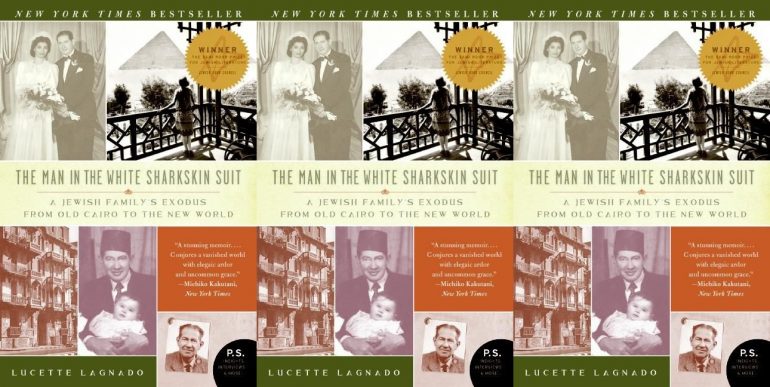

The American Dream in The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit

Lucette Lagnado’s family didn’t start off as public charges and refugees. Before coming to the United States from Cairo, the Jewish family had money. They lived in a good district. Lucette and her siblings were sent to private schools. The family had maids and ate out at European-style restaurants and patisseries. Before the fall of King Farouk, Lucette’s father, Leon, was a businessman who was fluent in seven languages, including English, which allowed him to act as a go-between with the then-colonial rulers of Egypt and the rest of Cairo, despite the fact that he was Jewish.

Leon’s family had come to Cairo from Aleppo, where they had, for hundreds of years, been known for their many rabbis and scholars. Leon experienced a similarly high status in Egypt. In Cairo, he wore an array of “expensive, hand-tailored suits,” including one made of white sharkskin, which was “all the rage among Cairo’s privileged classes” in the 1940s and 1950s, according to Lucette’s 2007 family memoir, The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: A Jewish Family’s Exodus from Old Cairo to the New World. His wardrobe also included tailored suits in linen, Egyptian cotton, tweed, vicuna, and silk imported from India. When the family left Cairo after the overthrow of the monarchy, amidst the expulsion and exodus of many Jewish people from Egypt, with only $212, they also took with them 26 suitcases and duffel bags full of clothes, many of which they never wore. This was the only way for them to take some of their wealth with them. Lagnado notes that like many other Jewish Levantine families, hers found itself suddenly without social status and wealth, having gone from “being solid members of the bourgeoisie to beggars” overnight.

The Lagnado family’s exodus from Cairo first took them through Paris, where the family was put under the charge of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and the Cojasor, an organization that had once helped victims of the Holocaust. Stubbornly, Leon insisted that the family be settled in the United States, and after months of pleading, the Lagnados arrived, in 1964, in New York. There, refugees were handed off to the New York Association for New Americans (NYANA) to get settled, which charged them with finding their own housing and becoming self-sufficient—as well as generally accepting American mores over their own.

The architect of this plan was Sylvia Kirschner, a NYANA caseworker in charge of the Lagnado family’s file who took an instant dislike to Leon. Kirschner seemed especially taken with freeing Lucette’s mother, Edith, and older sister, Suzette, from Leon’s perceived yoke. As Lagnado writes: “Leon could have been a criminal, a jewel thief, a philanderer, a swindler: nothing could have offended our social worker more than his refusal to conform and change and cast aside those values she clearly viewed as virtually un-American and utterly repugnant.”

Leon’s broken leg that would never heal and older age had originally made him an unattractive candidate for settlement in the US, and his attachment to the ways of Cairo and refusal to accept American ideas without question rankled the caseworker. Kirschner had settled thousands of immigrants in the course of her career, but his refusal to “abandon… belief systems that were quaint and out of date in favor of the modern, the new, the progressive ideas that were so uniquely American” put Leon, the “overly polite gentleman with the vaguely British accent” in the wrong box.

The expectation that refugees completely let go of their past lives feels slightly old-fashioned, but it isn’t far off from how immigrants and their descendants are treated in the US today. As Toni Morrison said in a 1992 episode of the TV series Without Walls, “In this country, American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate.” To Donald Trump and his supporters, New York State Assembly member Ron Kim says, to be American is to be “white and Christian.” The resurgence of widespread white supremacist violence highlights how important it is to read about the difficulties of immigration.

These difficulties are ever-present in the last part of Lagnado’s memoir, which chronicles her family’s move to Brooklyn. There, she quickly learns from her mother not to say that she’s from Egypt, to instead tell everyone that she is from Paris. She felt, she says, that she was “burdened with a dark secret that was bound to surface.” Her mother’s instruction protects her, however, until an awful landlord yells at the family, saying that they “‘would be better off in a tent in the desert’” because they don’t have the money to furnish their apartment.

The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit is a testament to the difficulties that are so inherent to the immigration process that even a family of people who are educated, upper-class, and well-off experience them. The bias that held back the Lagnado family in the 1960s has only grown worse, preventing so many immigrants from achieving the promise of the American dream: that if you work hard enough, regardless of where you came from, you will succeed.