The Power of the Cuban Peoples’s Verses

I’m sitting on the levee, watching the canal bleed into the Mississippi River. As I sit, I look at the other side, the West Bank, and I think of being down in Key West, where at the other side of southern waters is Cuba, the island that my father was born and raised in, that both sides of my family come from, was exiled from. I’m reading Margarita Engle’s 2008 collection, The Surrender Tree, about a healer, a nurse, living through Cuba’s independence wars against Spain in the nineteenth century. I’m reading this book, by a Cuban-descended woman, from the perspective of the Cuban people on the island, because I understand the importance of poetry for the people in Cuba. I understand the political power poets have had and still have in Cuba. I wanted to direct my energy and the narrative of Cuba back to the people of the island who have been fighting for a free Cuba; the best way I knew how, alone and away from the island, was with poetry.

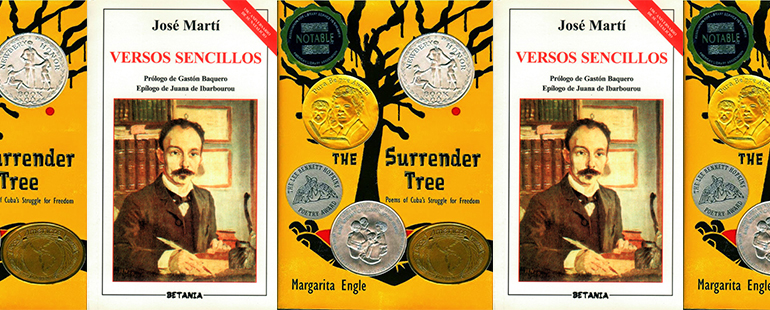

Poets and freedom fighters have always been important in Cuba’s history. The most well-known patriot and martyr of Cuba, José Martí, was a poet. Martí helped galvanize and unify a people through his poems. He helped introduce me to poetry, as well—my father showed me the poem “Cultivo Una Rosa Blanca” when I was a child. Margarita Engle recognizes this tradition, this history, in The Surrender Tree: in one later poem in Engle’s collection, the protagonist, Rosa, says that “tales of suffering sell newspapers that make readers feel safe, because they are so far away from the horror”—politics made the papers feel like propaganda, but poetry was from, and for, the people. Engle uses both her own ancestral history (her family members were refugees from the camps the Spanish maintained during the Cuban Independence wars) and anthropological information (Rosa and most of the other main characters in the collection were real, and they are heavily researched) throughout The Surrender Tree to tell stories of the island that don’t support the narratives—propagated by both the U.S. left and right—that abound when discussing Cuba from afar. Her poetry brings the narrative back to the people.

While Martí helped set the precedent for writing about a free Cuba through poetics, and Engle joined that tradition in her writings about Cuba’s independence from Spain, the San Isidro Movement is the biggest movement currently fighting for a free Cuba—a Cuba free from Spain, the United States, and the current regime. The San Isidro Movement (named after a neighborhood in Havana where many of the artists and activists live and meet) has been speaking out against the arrests being made against the political opposition, about the perpetration of crimes against humanity and restrictions on freedom of speech, about the conditions that the people are suffering under in Cuba. The San Isidro Movement only grew bigger after the Cuban government’s passing of Decree 349, which made any poetry or art that had not been “approved” by the government illegal. The government knows the revolutionary history and power of artists and poets in Cuba, and they fear it.

Some of that power can be found in the song “Patria y Vida,” which riffs off the Cuban government’s slogan “Patria y Muerte,” performed by Gente de Zona, El Funky, Yotuel Romero (of the hip-hop group Orishas), Descemer Bueno, and Maykel Osorbo. The connections between hip-hop and poetry are strong and deeply rooted, as are the connections between oral storytelling and the people of Cuba. Engle chose to write these stories as a collection of poetry, making them easy to access for all readers. Martí, in his Versos Sencillos (1891), writes about the power of his poetry, saying, “My verse, short and sincere, / It is from the vigor of steel / With which the sword is fused.” Early in “Patria y Vida,” a verse states that the song is “my way of telling you / my people cry and I feel their voice.” These artists all know the importance and power of their verses.

Engle’s book tells the story of three of the wars fought for Cuba’s independence; she tells this story through the eyes of Cuba, a rarity in English literature—the United States calls these wars the Spanish-American War, completely erasing Cuba, its people, and its hoped-for independence, from their pages of history. Engle’s poems reclaim the narrative; they are mostly told from the perspective of Rosa, who was a Cuban nurse during these wars, and her partner José, who helped created hospitals and hide Rosa from the Spanish army. Engle starts The Surrender Tree with Rosa saying, “Some people call me a child-witch / but I’m just a girl who likes to watch / the hands of the women / as they gather wild herbs and flowers / to heal the sick.” This opening line introduces the fact that the narratives about Rosa are different than the reality. Rosa is fighting for her country and her peoples’s freedom. The line is also similar to the opening of Martí’s Versos Sencillos, which begins: “I am a sincere man / from where the palm trees grow.” Martí is not a politician, he says. He is sincere, and he is from here, so the people should listen to him. This appeal happens in “Patria y Vida” as well, when the Cuban band Gente de Zona, no longer living within the country they were born in, start by singing, “And you are my siren song / Because with your voice my sorrows go away / And this feeling is already stale / You hurt me so much even though you are far away.” All of these poems, written decades apart, use similar techniques, bringing these stories back to the people for a free Cuba.

One of Martí’s more renowned poems is “Cultivo Una Rosa Blanca,” which reads (translation by me): “And for the cruel person who tears out / The heart with which I live, / I cultivate neither nettles nor thorns: / I cultivate a white rose.” Martí wasn’t going to allow his country’s colonizers, his peoples’s oppressors, to take away the beauty of his life. So he creates a white rose, a poem, for both his friends and his enemies. This feeling is echoed early in Engle’s The Surrender Tree, when Rosa helps heal Lt. Death, a character based on slave catchers operated during the independence wars. Lt. Death lives, but despite Rosa’s kindness, he hunts her for over the course of the entire book. In “Patria y Vida,” I hear: “Today I invite you to walk through the home of my ancestors / To show how your ideals have served us / We are human, even if we don’t think alike / let’s not treat each other like animals.” In this poem, I hear the bleeding for one’s home, a bleeding that was true of the people fighting for a free Cuba over a century ago. These lines connect more strongly with me than any manifesto of what Cuba should be, any doctrine written by people hiding behind the borders of water and language, or in a fortress surrounded by a police state protecting them from their own people. These lines of these poems get stuck in our heads, played over and over again.

In The Surrender Tree, Rosa says, “This new war begins with rhymes, the Simple Verses of Martí, Cuba’s most beloved poet. José Martí, who leads with words, not just swords.” Martí wrote that his verse was made of the same metal as swords; his words inspired a country to free itself from the shackles of colonizers. Martí was considered a poor—at best—soldier, but he helped Cuba win a war with his words. And now, in a country where the people have little means to protest against their own government, Cubans are still protesting with poetry, with the power of their words. In every moment in The Surrender Tree where Rosa or José or Silvia are quiet, Martí’s words feel present. In every moment in “Patria y Vida,” the peoples’s voice is present.

Rosa talks about people huddling around candles reading Martí’s Versos Sencillos, the “poet of memory, our memory of hope.” Martí’s poems are still read in schools in Cuba, as if being free from colonizers makes them free from the horrors of their own regimes. Engle’s book, written with simple lines that could be accessed by children—children of exiles who stumble over the language of their ancestors’ homeland—is full of poems that are layered. They are meant for adults to enjoy, but also to give them a resource beyond history books; they teach and share the struggle of Cuban freedom fighters. The first time I took a taxi from José Martí airport to Havana, the “Country or Death” billboard lorded over the road before us. I remember wondering if my father would be able to make it back to the country, or if the phrase would burn him from his childhood memories. In “Patria y Vida,” I hear, “No more lies / my people ask for freedom / no more doctrines / Let’s no longer shout ‘Homeland and Death’ but ‘Homeland and Life’ / And start to build what we dream of / what they destroyed with their hands.” With these lines, the musicians created an anthem that the people could recite—one that centered themselves, not a movement that has killed so many of them, exiled so many of us.

Now it is night and I am alone, feeling helpless in my isolation and far away from my family, and the home they’ve lost and never recovered. I think of the mentiritas of the Cuba Libres that used to haunt mi abuelo. I think of the billboards that would haunt my father. I think of how I’ve never been to Cuba with the members of my family that were physically uprooted from their homeland. I think of how in so many political conversations, there is no room for the actual people on the island to live, everyone having to fit into a Country or Death decided by the fewest and the worst of so many of us. I think of how Martí died before he got to see a Cuba free from Spain, but how his poems still live, still fuel the people, still help fight the oppressors. I think of how even if this regime pimps out Martí’s name and poems, so many Cubans don’t feel free.

Near the end of The Surrender Tree, Silvia, a young girl who had heard rumors of Rosa’s healing power, links up with Rosa and José. At one point, she falls asleep, “dreaming of music and friends, not food. I fall asleep with my whole family all around me, still alive.” I think of what it would take for my family, for all of those stuck on the island or exiled, to all be home and free together, on the island. I think of how it’s so hard to see that day, with the United States keeping its blockade, and Cuba’s current president continuing to repeat the same Castro and Communist lines about a “better Cuba.” More and more time is getting added to the distance and barriers already between us. But these poems, these songs, keep living, and they keep repeating in the minds of those stuck on an island where they could be prosecuted if they speak their truth. They keep repeating for those of us who can’t so easily return to the land we or our families come from. They keep repeating, “Home and Life,” capturing the voice of the people— not for one party or the other, but for you, for me, for the people.