Pursuing Essence through Ambiguity: On Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories

Among the known instances of writers reworking published material, Japanese author Yasunari Kawabata stands apart for his seemingly untenable decision to turn his acclaimed novel Snow Country (for which, along with Thousand Cranes and The Old Capital, he received the 1968 Nobel Prize) into an eleven-page story. Kawabata completed “Gleanings from Snow Country” just three months before his death in 1972. Yet while the story pulls scenes almost intact from the novel, it does not offer a condensed retelling. Rather in his distinctly spare yet affecting style, Kawabata’s miniaturization intensifies the isolated images, producing an independent take on his regarded masterpiece. In excavating new facets of his novel, Kawabata was also returning to the form he felt encapsulated his art: a series of short works he eloquently described as “palm-of-the-hand stories.”

Palm-of-the-Hand Stories, translated by Lane Dunlop and J. Martin Holman, contains 70 of the 146 brief vignettes Kawabata wrote across the span of his career. While “Gleanings from Snow Country” is unique in its novelistic origins, the other works in the collection—most only a few pages long—evoke an urgency and substance that makes a similar adaptation conceivable, albeit in reverse. That Kawabata achieves such intricacy in a concise, understated manner supports an initial temptation to compare his palm-of-the-hand stories to haiku. The fantastical nature of some of the works—gravestones tumbling down hills like white goblins, lionhead goldfish swimming through a silvered mirror, a woman who turns into a lily—also suggests the possibility of placing them along the spectrum of fairytale. Certainly, the judicious imagery and inventive associations found within the stories are reminiscent of prose poetry or flash fiction. Yet as I moved through the collection, considering what made the remarkably varied works still feel cohesive, I determined that the palm-of-the-hand stories are a form all their own, difficult to measure against more familiar conventions. This conclusion was useful only to the extent I could admit I did not yet know, exactly, how to approach them.

One shared characteristic of Kawabata’s palm-of-the-hand stories is their ambiguity. Though evident across the ample collection, this is more prominent in some instances than others. While events occur without context in “The Grasshopper and the Bell Cricket,” for example, the significance of trembling patterns cast by the aperture lanterns of “wise child-artists” is immediately discernible, offering one of the most striking considerations of innocence I’ve ever read. In “Earth,” on the other hand, meaning is more elusive, the story written in nine segments where leaps between points of logic don’t quite connect. In still other stories digressions take over and become the second half of the narrative, or incongruities accumulate to the point of feeling coarse. Such subtly can easily plunge the brief vignettes into shadow territory: the minimalism becoming too extensive to provide a readable map, the understatement edging past clarity toward confusion.

At first, I felt frustration with this elusiveness. The implication of such nimble works seemed to be that they would readily provide insight, answers. That I could dip into the palm-sized worlds of mountain hot springs, Kyoto dancers, and moon-viewing bridges and discover new understanding with ease. And to be sure, I felt without doubt that the stories had volumes to teach me: Kawabata’s tangible depth of attention to the subterranean, to the import of the unspoken, made the stories impossible to discard.

In this respect, reading Kawabata’s palm-of-the-hand stories recalled for me the experience of gazing at “magic eye” images: those pixilated graphics that promise a three-dimensional shape will reify only if you can learn how to look at them right. I had to adjust my gaze, try out a different mental lens, for the material to come into focus. At the same time, I also realized that the stories don’t necessarily contain one single meaning to extract. Rather than functioning as a parable might—presenting clear-cut morals to take away, useful for applying to the real world—the palm-of-the-hand stories draw latent knowledge from the reader: hidden gems of truth already possessed. By pursuing the essence of a plot, its fundamental unit of narrative, the stories generate contours spacious enough to encircle vast arrays of lived experience. This is the uncanny magic of Kawabata’s form: a deceptively small structure with limitless storage capacity. It is precisely their ambiguity that invests the palm-of-the-hand stories with deeper meaning, their irresolution that exquisitely reflects the near-infinite, interior epics of life.

One of Kawabata’s earliest works, “The White Flower,” is indicative of this value in ambiguity—namely, that it retains possibility for all the things we can’t quite fix to the world with words. In the story, a woman encounters a series of men who are startlingly overbearing in their affection, desperate to possess the entirety of her existence. “If medicine weren’t my calling from heaven, my emotions would have killed you by now,” says a doctor who helps cure her of tuberculosis. Later, the girl runs into similar trouble while on vacation with a novelist. Yet while the writer expresses his desire to wholly render the girl on the page—for her to live in his novel, as it were—he acknowledges the impossibility of doing so, the futility of capturing “the transparent beauty of characteristics that are no characteristics at all.” “You bring a beauty like a fragrance that you can’t see with the naked eye, like the pollen that perfumes the spring fields,” he tells her. “How shall I write it?” It is not a task he can accomplish on his own, or to completion. Still, the novelist is moved to make the imperfect attempt: “Put your soul in the palm of my hand for me to look at, like a crystal jewel,” he says. “I’ll sketch it in words.”

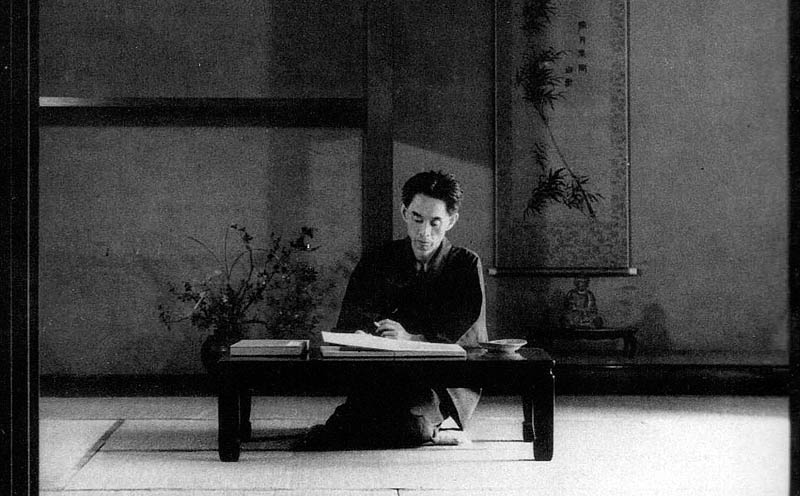

Photo: Kawabata at work in his home in Kamakura, Japan (1946)

About Author

Lara Palmquist is a Rotary Global Grant Scholar living in Sweden, where she is a graduate student at Uppsala University. She is originally from Albuquerque, New Mexico. You can find her on Twitter @LaraPalmquist or at www.larapalmquist.com