Reconstruction: How the Lyric Essay Rendered One Body After Trauma

1.

I didn’t start writing lyric essays until I found out I had cancer. The melanoma buried in my right cheek was at first missed, and then misdiagnosed in its severity. Clark’s stage IV, they told me. Likely in my lymph nodes, but they wouldn’t know until my third surgery, the excision and biopsy.

2.

I was coming out of a dry period in my writing. I had hardly written in the previous year since my brother’s death from complications arising from a rare genetic disorder. When I went back to the page, I couldn’t go back to it as I’d been there before, but I felt I must go back. I had something to say, and what if I didn’t have long to say it?

What If became my muse.

3.

The poems became fragmented, full of white space. I broke lines unexpectedly, at least for me. Out of tune, out of sync/syntax. I revised through redaction, cuts, excisions. Everything seemed relevant and connected, even as everything seemed disjointed. Separate.

4.

Text is solid or liquid, body or blood.1

5.

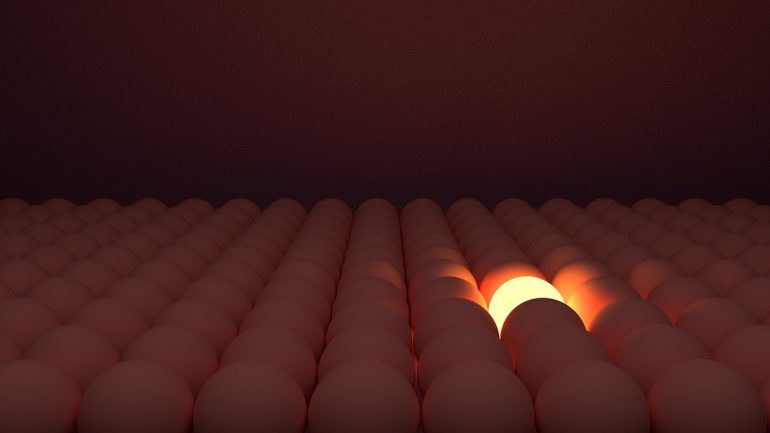

Nothing seemed explicable, and so I refused to do the expository work of making meaning. Things just were, or I was afraid they were. Every statement seemed loaded through its silent conversations with other statements. Juxtapositions ruled by oligarchy: before/after, life/death, yes/no, disfigurement/reconstruction, me/you.

6.

Have you seen the fool that corrupted his own live body? or the fool that corrupted her own live body?

For they do not conceal themselves, and cannot conceal themselves.2

7.

Trauma, or rather fear, sweeps. It guts. It zooms in, even as it backs up. It hurricanes. Needles. Jabs. Sticks. Stomps. Irradiates. Gets in your face. Looms just out of sight. It’s an in-between, a joint-stock no man’s land. Chimerical, it needs hybridity, thrives off of it.

8.

Yale Cancer Center scientists, together with colleagues at the Denver Police Crime Lab and the University of Colorado, have found evidence that a human metastatic tumor can arise when a leukocyte (white blood cell) and a cancer cell fuse to form a genetic hybrid.3

9.

The lyric does this…the reader is immersed in language and synthesis: the knowledge that what we are being told is true, yet the way we are being told these truths are masked in some sort of artifice—that instead of being immersed in narrative and plot, we are immersed in structure: what words repeat themselves, the speed of the language varying, phrases meant to express the intangible in a tangible way.4

10.

After the surgeries, I looked at myself in the mirror every day. I took pictures of my face, swollen, going down, hollow. The act of writing, of laying it all down in the form of a lyric, became my act of turning my whole body and its contingent thoughts, emotions, deceptions, candor, and fears to the mirror, of stilling it. And stealing it back.

11.

I’ll wash my hair, then what,

try to wake up from all this. 5

12.

Every time I wrote I felt like my writing became a body in which I was trying to make my stand, to live.

In “Excisions,” a lyric essay about my experience with melanoma, I write: “Something I wasn’t, something I already was: the best definition of cancer I’ve come up with.”

The reconstructive surgeon pulled from my stomach to reshape my face.

To pull from one part of the body to repair another.

To become fragment to feel whole.

To pull from poetry to shape the essay.

13.

I admit it: / this body’s not enough for me.6

1Ellen Lupton, Thinking with Type

2Walt Whitman, “I Sing the Body Electric”

3Helen Dodson, “How cancer spreads: Metastatic tumor a hybrid of cancer cell and white blood cell,” YaleNews

4Roxane Gay, “Manipulations of the World: On the Lyric Essay,” LitPub

5Wisława Szymborska, “Identification” (trans. Clare Cavanagh and Stanslaw Baranczak), Poetry

6Gabrielle Calvocoressi, “Praise House: The New Economy,” American Poetry Review

About Author

Emilia Phillips is the author of three poetry collections from the University of Akron Press, most recently Empty Clip (2018), and four chapbooks, including the forthcoming Hemlock (Diode Editions, 2019). Her poems and lyric essays appear widely in literary publications including Agni, American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, Poetry, and elsewhere. She’s an assistant professor in the MFA Writing Program and the Department of English at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.