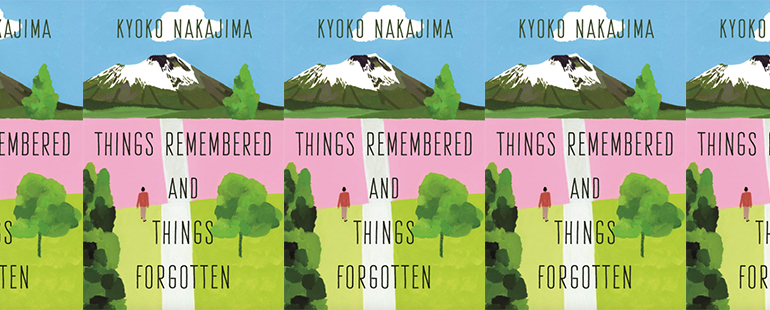

The Exploration of Memory in Things Remembered and Things Forgotten

Kyoko Nakajima’s short story collection Things Remembered and Things Forgotten, published in English translation by Ian MacDonald and Ginny Tapley Takemori earlier this year, explores themes of memory and all that accompanies it—grief, joy, discovery, and so on. At the same time, Nakajima’s stories reveal the fallibility of memory, the ways we tend to retcon our pasts or histories to construct stories for ourselves and others. The collection itself is not a translation of a pre-existing collection of short stories published in Japanese; instead, it is a compilation of a number of Nakajima’s most popular works, put together in a new combination for English readers around the particular themes Nakajima is interested in. These stories, considered together, create a glimpse into the ways we construct our memories, and the ways we forget—through the natural process of time, and even deliberately.

The title of the book is taken from the first story in the collection, a story that moves between the present—when Masaru and his wife visit his older brother, Takashi, in a memory care facility—and the past—Masaru’s memories of World War II Japan, when he and Takashi were children. Throughout the story, Nakajima deftly reveals the brothers’ relationship through the conversations that Masaru has with his wife, as well as through Masaru’s own private recollections. There is a sense that readers are supposed to focus on Takashi’s inability to remember in contrast to Masaru’s still intact memories, as in the case of many stories that center on individuals with Alzheimer’s-like health conditions. By the last page, however, Nakajima has provided a stunning twist forcing readers to reconsider what a memory is. The real Masaru, it turns out, died in the final year of the war; the Masaru of the story is an abandoned young boy that Takashi and the real Masaru come across throughout the story, who then takes Masaru’s place. Nakajima writes, “Towards the end of the year in which the war ended, Masaru died. He caught a cold that turned into pneumonia, and he was too malnourished to recover. It was something Takashi remembered but Masaru had forgotten.” When is a memory considered real? she asks. Does it matter whose memories we are considering? Does someone else telling a story still make the memory true? Like the collection itself, “Things Remembered and Things Forgotten” is playful about the subject doing the action; the story’s title similarly avoids directly stating who is doing the remembering or who is doing the forgetting, stating instead simply that these actions have happened.

Throughout the collection, memory is not only held or constructed by human beings—it is also infused into objects. In “The Life Story of a Sewing Machine,” readers enter the story from the perspective of Yuka, who happens to see a sewing machine in the window of an antique shop as she walks to and from work. The shopkeeper eventually convinces her to come inside and, after looking at a few odds and ends, she sees another sewing machine in very bad shape: a Model 100-30 made by a Japanese company in the 1920s. Suddenly, readers are whisked away from Yuka and the shopkeeper and placed directly into the memories of the Model 100-30. The language elucidating the sewing machine’s account is humorously similar to a human biography: “The Pine Model 100-30 was born and raised in Tokyo’s Kitatama district, but no sooner was it given the stamp of approval to go out into the world than it was packed off to the dressmaking school in the factory grounds,” Nakajima writes. The sewing machine’s biography highlights the importance of histories that humans may have forgotten—like the simple Model 100-30, some histories are considered less important than others. The sewing machine was never connected to a key historical figure; instead, it witnessed the experiences of those considered lower in the social hierarchy: young girls who needed to learn a new trade, women who were going through domestic training in preparation for marriage before the war, and widows in the post-war era who needed to take on sewing in order to collect enough money to survive.

Throughout this section of the story, the reader stands in the balance, obtaining an objective, overhead view of the Model 100-30’s history as it passes from various institutions and homes through the 1920s and into World War II, while also gaining insight into its emotional attachments to these people and places. The story doesn’t just provide a dry history with an object as the rhetorical vehicle—it highlights the machine’s emotions attached to these memories. When the sewing machine experiences the firebombing of Tokyo, for example, it recalls the flames in vivid detail, along with its emotional response: “For the sewing machine, with a dignified bearing and fated to be stationary, the shock all but caused it to lose its reason for existence.” In other moments, it describes being “buried alive” and, elsewhere, expresses some regret that it will never see some of its previous owners again. Though the account isn’t given in the first person, these memories are presented as the memories of the sewing machine itself. The story never even returns to Yuka and the shopkeeper, ending instead on the Model 100-30’s memories of the death of its previous owner. This biography format creates a sense of importance, both for the sewing machine and the women it came into contact with, the memories of their lives linked together not only by history but by objects they came in contact with. The reader comes away with the feeling that these stories deserve to be told, even if the only thing that remembers them is a sewing machine. In this way, like “Things Remembered and Things Forgotten,” “The Life Story of a Sewing Machine” blurs the line between what memories are, and who (or what) makes them.

While Nakajima explores memories infused in objects, she also touches on a more common conception of memory as infusing a certain space. A number of the stories in the collection depict ghosts and explore how they interact with the world of the living. Some ghosts are tied to specific buildings or homes, while others are able to move more freely within a city. In each of these ghost-related stories, the ghosts act on their past memories—they often want to visit a place of significance on specific holidays or key anniversaries—and, in doing so, are able to create new memories. In “Kirara’s Paper Plane,” for example, we meet Kenta, a ghost who materializes periodically in the world of the living. He blinks out of existence between each return, but is able to retain the memories of his past and of each subsequent return. As a result, we understand that Kenta is continually making new memories, such as when he befriends a young girl, Kirara. But there is also a murkiness to Kenta’s existence, a question about what allows him to reappear in the world of the living in the first place. At one point, Nakajima writes, “It occurred to Kenta that after the memory of his existence had faded completely from the minds of those who had known him, his appearances, too, might cease altogether.” Even for ghosts, it isn’t clear how memory functions—they hold their own memories but might also be made up of the stuff of others’ memories, too. A similar situation occurs in the story “The Last Obon,” in which a family gathers to celebrate the Obon festival together, in honor of their mother who has passed away. As the living remember the dead, they are visited by several ghosts who come to pay their respects to the mother, expressing their sorrow that she had passed away. Though they themselves have been dead for several years, they return to reminisce fondly with those who are still alive. In the case of the ghosts of Nakajima’s stories, memories seem to linger long after death, drawing spirits back to both locations and people.

Things Remembered and Things Forgotten provides an engrossing and unique exploration into our understanding of memory. In the collection, memory isn’t a centralized thing; it is at times personal, a singular emanation from a person or object, and at other moments is a broad field, multiple consciousnesses moving through it. While the objectivity of memory—and even its actual substance—is consistently brought into question in her stories, what remains clear are the emotions attached to the act of remembering and the way these emotions meaningfully link individuals or objects across time.