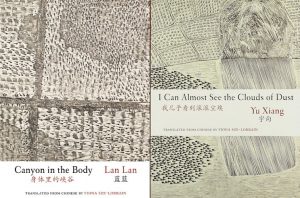

Canyon in the Body by Lan Lan and I Can Almost See the Clouds of Dust by Yu Xiang

In Canyon in the Body by Lan Lan (b. 1967), translated from Chinese by poet and musician Fiona Sze-Lorrain, the speaker bears witness to reminders of the natural world in the midst of personal and mass misfortune. Sometimes indignant, at other times resigned or awestruck, the speaker’s observations add up to more than their parts. Take the destruction and regeneration in a lopped-off sunflower head, and the ferocity of the speaker’s realization of its betrayal, in “Wild Sunflower”:

Old past veiled in sorrow, for whom have I died once more? Untrue wild sunflower. Untrue singing. A lethal thorn of autumn wind pricks my chest.

The extended poem “A Few Grains of Sand” also wonders about the idiosyncrasies of private mourning, now in contrast with the vague broadness and metaphorical representations of public mourning—how people “prefer objects that flatten everything. With pebble bread on top/draped in black cloth” versus mass suffering often depicted as “Newspapers: hostages. Weapons. Death tolls./Each nationality occupies a page.” or as a symbol: “A bird alive in shrapnel/strikes a poet’s stupor”. The speaker, however, is left disarmed by her very literal fortune:

Sometimes I just can’t understand my steamed bun my rice and the dust on these bookshelves. I kneel. My ego bends.

and is offered remedies such as birth as a miracle and an illusion: “the earth’s first love letter./ One and countless./ — Please continue the concert —” (“Mother”), or disintegration as a means to eternity (“Wind”): “Wind empties him little by little./He becomes sand grains . . . Wind lets him live forever — ”.

At other times, the poems explain their comparisons to the natural world a little too much, dulling the magic of a comparison. In “Persimmon Tree”: I wished that the metaphor of the persimmon tree with five red fruits were not pinned down so hard: “dear, it is/this city’s humanity.”

Fruit and flowers won’t be ignored. Anthropomorphized, they unfold themselves to the speaker throughout the book, in poems such as “Lily”, “Rose”, and “Four Kinds of Desert Plants”: “She does not reign. Or envy,” the speaker observes the oleaster, “She is the appearance she needs not dream for.” Of the camelthorn, “The desert brings about the leadenness of truth/to be pierced by her slightest courage.”

Why would the speaker, in the face of adversity, not then choose to watch and record each source of joy?: “Years later, someone will jump from that tree/carrying the whole of Heaven Lake/rushing to save me from the vast desert” (“Sky Mountains”).

* * *

In I Can Almost See The Clouds of Dust, also translated by Sze-Lorrain, Yu Xiang (b. 1970) conveys moments that are transformative—such as a brief imagining of a herd of cattle on a city road kicking up dust in the title poem below—and moments that can never be, such as the death of children in a collapsed school building and officials’ ineffectual apologies after earthquakes and mudslides. At the same time, the speaker holds onto moments of daily ritual or its unexpected halting as people depart, such as in “Still Broad Daylight”, “Sunlight Shines Where It’s Needed” , and “The Key Turns in the Keyhole”, where the speaker is surprised by her continued existence despite the departure of people, their habits, and the signs of their life.

Poems such as “Other Things”:

they say cooking porridge is easy I don’t think so because it makes me think of other things . . . you can’t stop stirring can’t think of other things if you stop, cornflour will stick to the bottom other sounds will reach your ears

and “I Can Almost See the Clouds of Dust”:

A herd of cattle walks on a tar road I imagine them stirring up clouds of dust If they run, startled I’ll imagine bigger clouds of dust . . . They come one by one They pass by me

reveal a sensitivity to Blake’s world in a grain of sand, if we remember what happens to his dove and dog. Contrastingly, the speaker describes the pointlessness of a process of creation in which coarseness, outmoded officialdom, and deterioration are curated and rearranged into souvenir-like art:

I must make up my mind to paint some outdoor scenes like going to work every day have to pass by those bloated strawberries and chickens pass by illegal books, sexual diseases, legends . . . I take down my forefathers’ awards and medals stained with glorious corrosion . . . For a lyrical feel, I arrange them again and again these still lifes, like the last nobles

Yu Xiang understands, says Sze-Lorrain in her introduction, that “narration is outmoded because it cannot catch up with time and lies.” Her external world isn’t an observed phenomenon or a muse, but rather a source of ways to describe the speaker’s disbelief and knowledge. In “The Rotten, The Fresh”, the speaker separating rotten vegetables from fresh ones sees that “both can’t live anew.” Captivated by objects for a long time in “Distracted”, she issues a paradoxical challenge to whoever is observing her: “I like staring at fleeting things/unaware that someone else is staring at me in this way.”

Yu Xiang bids us farewell for now in “At the End, You See Onscreen”, where the speaker describes a “great actor” in a “trashy drama” on TV as impossibly acting out “a performer of all roles/ a people / a people on its own.” The speaker might wonder at how common yet unattainable the goals of such entertainment are, if not an attempt at a book of poetry. And the writer and translator leave us unable to view a lone tree in the same way we may once have; transfixed, yet aware of our act of reading.

The books are available from Zephyr Press and The Chinese University Press of Hong Kong.