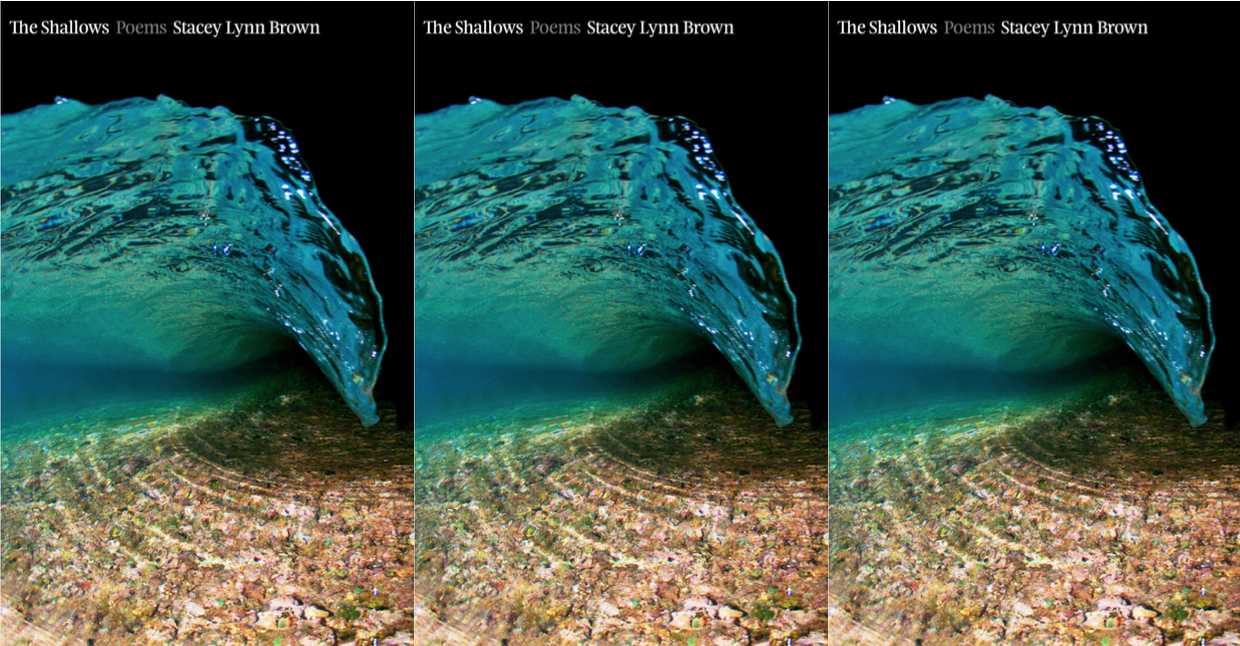

The Shallows by Stacey Lynn Brown

The Shallows

Stacey Lynn Brown

Persea Books | October 16, 2018

Embodiment and exploration of the physical body is a mode through which some poets have found a means of expressing both the grief and joy of being human. To this theme, Stacey Lynn Brown’s second book of poetry, The Shallows, offers a poignant exploration of the ailing body, and what it means to be chronically ill. Documenting the double decline of herself and her father, The Shallows utilizes the running metaphor of borders—the space between the sea and the shore, the movement between sickness and health, the dance between life and death—to discuss the sick person in relation to the world around him or her, and the sick body in relation to healthy bodies. In the long poem that runs through the middle of the book and bears the book’s title, the speaker explores the infinite push and pull of life that the sea represents, opening with an image of her aged father:

My father, wading out into the sea,

his pale legs bowed parentheses,

hair a dusting of once-black grey

above a body disappearing as he makes his way

into the blue green Gulf of Mexico.

Watching him, somehow I know

this is the last time…

The shorter poems within the longer poem “The Shallows” flow into each other, despite the difference in their forms, through the linking of the last line of one poem with the first line of the next. They remind readers, as the last poem within this long poem indicates, that all that will remain of the speaker’s father is the speaker’s memory of him:

…And even though I know it isn’t possible,

impossible, I still catch sight of him then, in the young man carefully making his wayaway from us, disappearing gradually, that diminishing figure that can only ever—

never again—be my father, wading out into the sea.

The beauty of so many of the poems in this book is visual aesthetic that, at times, creates flow, and at others, asks the reader to ponder what it means to live in the white space between words, between the speaker’s understanding of her father’s diagnosis and her own experience of going from doctor to doctor to understand her illness. In “Word Jumble: Aphasia,” readers are invited to experience how this language disorder works, by encountering a series of jumbled words that create the “cluttered / characters / arranged / and / rearranged” on the page. The work readers must do, the speaker suggests, is a tandem task the speaker and her father must perform—her father because of old age, and the speaker for mysterious medical reasons.

In certain poems, like the fourth poem in “The Shallows” (the long poem), readers may feel that the poem teaches them how to read it. Beginning with the line, “What lies ahead unfathomable as the unplumbed depths below,” the rest of this poem is a series of six columns of words, which trickle down the page, as if to visually demonstrate these depths. One column reads, “he / free / falls / through / the / darkness / like / I / once / plummeted / through / borrowed / sky.” In linking their illnesses together, the speaker also blurs the lines between caregiver and patient, roles that father and daughter have exchanged over time.

Just as sickness becomes akin to a physical location for authors like Flannery O’Connor (as explored in Angela Alaimo O’Donnell’s biography of O’Connor), so it does for Brown’s speaker. In “In the Country of the Chronically Ill,” the speaker finds kinship with fellow sufferers: “We / nod at the weariness in each / other’s sighs, forgive the last- / minute cancellation of plans.” These lines, enjambed as if spoken in short breaths, give way to the speaker’s latest symptoms, her faltering moment at what she thought might be the border of recovery, “until my cough, new sickness, / reclaimed me, standing / patient at the border, passport / stamped, welcomed home, / nothing to declare.” In part IV. of “Diagnosis,” it becomes clear that illness is at once a place and a lack of place—“The body’s wholesale / rejection of a place”—as the speaker struggles to find environments that support her health. Her options are limited, and doctors seem to suggest the impossible: “just avoid / context. Nature. And any / urge you may still have / to breathe this world in deep.”

The shallows, then, become not just a wading place, a space between shore and ocean, but a way of living. The speaker must not breathe deep, and her attempt to plumb the depths of her own illness leaves her searching for the right words, for a place beyond the fatigue, pain, and confusion that both she and her father are experiencing. The shallows become an immersion in a borderland that takes hold of the body. The speaker is at once the leader through this painful wilderness—for her father, she is “the key to his understanding of this / world, cartographer of the known / and patron of the voyage, benevolently / blessing his adventure, sending him / off sailing into waters unchartered”—while also the map upon which the wilderness takes hold. In “Abandoning,” readers glimpse the ravages of illness on the speaker’s body:

My hip

bones razor,

the steppes

of spine

rising reptilian

from a

latticed back

Though each of these poems embodies the heaviness of illness, their beauty is evinced in the pauses, the generous white spaces to be found in this book of poems. In exploring the thresholds between sickness and health, between death and life, The Shallows leaves just as much unsaid as it reveals. Though readers do not leave the book knowing the immediate fate of the speaker or her father, it is clear that we walk with the speaker along, as she says in the book’s final poem, “the border of two / worlds, between the berm that leads me back to town / and the slow drag of an ocean that will not let me go.” It is in this borderland that readers experience these poems.